- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

How Antimicrobial Resistance Threatens Neonatal Mortality Rates Globally

How Antimicrobial Resistance Threatens Neonatal Mortality Rates Globally

Neonatal mortality remains a major health challenge across the world, which involves neonatal sepsis and other related factors of prematurity. Though many strides have been done in reducing NMR, there is a need for more appropriate interventions and strategies directed towards addressing the rise in the escalation of AMR. Combating AMR will be critical in improving neonatal survival rates while giving each newborn a healthier start into life globally.

The newborn period is the key period for infant health, and the first 28 days of life are critically important-both for survival and as a base to set lifetime health and development. Neonatal deaths globally have witnessed a significant decline over the past couple of decades. The neonatal mortality count has significantly reduced dropping from a high of 5 million in 1990 to as low as 2.3 million as of 2022. However, this decline notwithstanding, neonatal mortality is still staggeringly high across low-and middle-income nations.

Neonatal mortality rates are 22 per 1000 live births in India. Neonatal sepsis and prematurity are the main causes of neonatal deaths in these tragic events. Recognizing the gravity of the issue the Indian government started the Indian Newborn Action Plan (INAP) in 2014. The goal is to take NMR down to the single digits by 2030. This initiative has brought in several key interventions, including antenatal care (vaccines, micronutrient supplementation), skilled birth attendance, clean birth practices, and neonatal resuscitation techniques. More promisingly, postnatal interventions, including early initiation of breastfeeding and skin-to-skin contact, have been proven to work well in improving newborn survival rates.

Despite these improvements, one of the biggest concerns in neonatal care today is the growing problem of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) which seriously threatens efforts to reduce neonatal mortality.

What is Antimicrobial Resistance?

Antimicrobial resistance occurs when microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses and fungi evolve over time and become resistant to commonly used antibiotics and other medications. This resistance makes infections more difficult to treat, increasing the risk of mortality and complicating treatment options. The World Health Organization has classified AMR as one of the most urgent global health threats since it not only causes death and disability but also places immense pressure on healthcare systems, significantly raising the economic burden.

The sources of AMR are many, including poor hygiene and infection control in healthcare settings, overuse and misuse of antibiotics. Contributing factors to this rapidly growing problem are antibiotic prescriptions for patient needs that do not require them and failure to complete antibiotic courses, as prescribed.

AMR and Newborn Health

For neonates, the risk is much more vital for AMR. Neonates are particularly prone to developing infections due to their rather weak immune systems. Neonatal sepsis, severe bacterial infection, is one of the leading causes of neonate deaths and it often manifests complications when it is because of drug-resistant pathogens.

According to Dr. Apoorva Taduri, Consultant Neonatologist, "Neonatal sepsis accounts for a significant proportion of neonatal deaths, and AMR is making it worse. MDR pathogens cause around 30% of neonatal sepsis mortality globally.

Maternal health and care are also factors influencing AMR in neonates. Over-prescription of antibiotics during pregnancy increases the risk of neonatal sepsis and the development of multi-drug-resistant pathogens in newborns. This calls for prudent use of antibiotics during pregnancy and at the time of delivery. In fact, studies indicate that indiscriminate use of antibiotics in mothers has a direct impact on neonatal health, which may eventually lead to resistant infections in newborns.

One of the major issues is that the drug-resistant bacteria are causing an increasing number of healthcare-associated infections in the neonatal care settings, which include NICUs. Infections by such bacteria prove to be challenging to treat; they require more advanced, expensive interventions, and the period of risk of mortality and morbidity is extended.

Counteracting AMR in Neonatal Care

To combat AMR and reduce neonatal mortality a multifaceted approach is necessary. Dr. Taduri emphasizes the continuation of the strategies outlined by the Indian Newborn Action Plan (INAP), specifically in reducing neonatal sepsis and improving infection control. However, to combat AMR more must be done to ensure proper use of antibiotics in both maternal and neonatal care settings.

Key strategies for reducing AMR in neonatal care are:

1. Improving Infection Prevention Practice: This implies, therefore, that more efforts would be made regarding stricter hospital hygiene standards, strict equipment sterilization after its usage and even maintaining adequate hand hygiene. Enhanced infection control practices greatly impact minimizing AMR pathogens distribution.

2. Antibiotic Stewardship- Teaching the healthcare providers how not to use antibiotics is a crucial thing in preventing overuse prescription. Antibiotic stewardship programs are designed to promote use of antibiotics only when truly required; appropriate drug, dose and length of treatment should be taken.

3. Improved access to WASH: Access to clean water and sanitation is a fundamental aspect of preventing infections in mothers and newborns. WASH interventions such as clean birthing practices, can reduce the risk of neonatal sepsis due to unsanitary conditions.

4. Maternal Health Strengthening: Proper maternal care, such as proper vaccination, antenatal steroids, and supplementation of micronutrients, can reduce the risk of prematurity and neonatal infection. Prevention of infection in mothers is the first step towards prevention of infection in newborns.

5. Early Diagnosis and Treatment: Early identification and treatment of neonatal infections are very important. This includes proper screening for sepsis and the use of appropriate antibiotics based on the local resistance patterns. It also involves ensuring that infants receive adequate neonatal care, such as those provided in Special Newborn Care Units (SNCUs).

The rise of antimicrobial resistance is a global health challenge that requires urgent action. Combating AMR requires a coordinated effort from governments, healthcare systems and communities worldwide. In neonatal care, addressing AMR is essential to further reducing neonatal mortality rates and ensuring that every newborn has the opportunity to thrive.

As Dr. Taduri concludes, "While we have made substantial progress in reducing neonatal mortality, the emerging risk of antimicrobial resistance creates a major challenge for our efforts. Combating AMR requires a global collective effort, with priorities on infection prevention, responsible use of antibiotics, and enhancement of healthcare practices to ensure a healthier future for all newborns."

Dr Apoorva Taduri is a Consultant Neonatologist at Fernandez Hospital

Danica McKellar Said She Loved How Her Placenta Tasted; Why Do Some People Eat It?

Credits: Wikimedia Commons

Danica McKellar, American actress said she was embarrassed to admit that she liked tasting her placenta. While she did not go into childbirth thinking she was going to taste her placenta, she says she is glad she did so.

She said this while explaining her surprising postpartum culinary experience in a conversation with Bobby Bones on The BobbyCast.

"My doula said, do you want to taste the placenta? I'd just given birth. And I'm like, sure. I mean, you're not even, you're not in your right mind. She gave me a piece of it. Bobby, it was like the best filet mignon that I have ever tasted. But more," she said.

She continued that she was embarrassed about how much she loved it. "It was bizarre. I thought, what is this, some sort of weird satanic...Am I a cannibal?"

She is now mom to 15-year-old son Draco Verta, who she shares with her ex-husband and composer Mike Verta.

Why Do People Eat Placenta?

A 2014 BBC report notes that placenta sustains life in the womb and leaves the mother once it has served its purposes after the childbirth. The nutrients that have passed from mother to fetus over the months of pregnancy are still packed inside the placenta and should not be wasted. Instead, the raw placenta, many believe, could provide what the mother needs to recover from childbirth and begins breastfeeding.

Some women, as the BBC report notes, are also choosing to drink the placenta in a fruit smoothie within hours of giving birth. While others keep it cool and send it off to be dried and made into capsules, or ripping chunk of it and placing it by their gums.

As per Mayo Clinic, some people believe that eating placenta can help them recover from postpartum depression. However, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a warning against taking placenta capsules. The warning was based on the case in which newborn developed an infection called group B streptococcus after the mother took placenta capsules.

The mother was thought to be infected with group B strep bacteria that came from the placenta because the capsules tested positive for the bacteria. Then the infection spread to the infant. Group B strep can cause serious illness in newborns. That may include a severe infection called sepsis. Group B strep also can lead to meningitis. Meningitis is an infection that affects the lining of the brain and spinal cord.

This infection happens when one processes their placenta and it could expose the placenta to bacteria or viruses.

Placenta And What It Holds

The placenta contain several hormones, including oxytocin, estrogen, progesterone, and relaxin. It is also rich in protein, amino acids, and minerals. However, the claims of people saying that it is healthy and should be consumed after delivering a child to avoid postpartum depression have not been fully tested. There are however cases where animals other than humans eat placenta after birth as it could reduce there labor pain. However, the same has not been proven in humans.

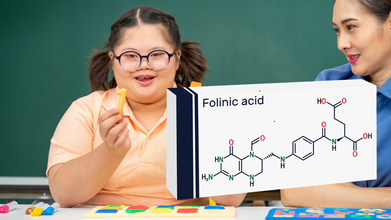

Leucovorin Prescriptions Surge After White House Mentions It For Autism Use, Parents Struggle To Find Drug

Credits: Canva and iStock

Leucovorin, a high-dose vitamin - folinic acid, were mostly used for treating toxic side effects of chemotherapy, until last year when the White House touted it as a potential treatment for some children with autism. New prescriptions for leucovorin double within weeks of announcement and parents have been trying hard to get it prescribed. This is also because many doctors have been hesitant to prescribe a chemotherapy medicine for childhood autism. They have also stated that not enough evidence is available to prescribe this drug officially.

CNN reported that in Austin, Texas, Meagan Johnson spent four days calling pharmacies across the region searching for leucovorin for her three-year-old son Jack, who has autism. She contacted nearly 40 pharmacies around her home in Pflugerville, hoping to locate the medication.

The effort came after a neurologist agreed to prescribe leucovorin on a trial basis. Johnson’s hope was simple: even a small improvement in her son’s communication would mean a lot. At age three, most children can say hundreds of words, but Jack speaks only about 20, many of which only his mother understands.

However, getting the prescription turned out to be far harder than obtaining it.

Across the United States, pharmacies have been reporting growing difficulty keeping leucovorin tablets in stock. Online support groups for parents of autistic children are now filled with posts from families searching for the medication or asking where it might still be available.

Although leucovorin is not approved specifically for autism, some small studies have suggested that it may help certain children who have unusually low levels of folate in the brain. Families who have tried it report possible improvements in language and social interaction.

A study published in The Lancet found that prescriptions for leucovorin doubled within weeks of the public remarks and remained elevated through early December. Researchers analysed electronic medical records covering nearly 300 million patients to identify the trend.

Experts say such spikes can quickly strain the supply of inexpensive generic drugs.

A Classic Demand-Driven Shortage

Pharmacy supply specialists describe the leucovorin situation as a demand-side shortage. Unlike manufacturing disruptions, these shortages happen when demand rises faster than manufacturers can increase production.

Generic drug manufacturers typically plan production schedules a year or more in advance. Because leucovorin had historically been a niche medication, companies were not prepared for a sudden surge in prescriptions.

As demand increased, pharmacies began running out of tablets. Many manufacturers have placed the drug on allocation or backorder, meaning pharmacies can only order limited quantities.

To ease the pressure, the US Food and Drug Administration allowed temporary imports of leucovorin tablets from Canada and Spain. However, the drug has not yet been officially listed on the FDA’s national drug shortage database, a designation that could trigger additional measures to boost supply.

Families Searching For A Treatment

For parents like Johnson, the debate over research evidence matters less than the possibility of progress.

After days of phone calls, a CVS pharmacist finally located a supply at another branch nearly an hour away. Johnson drove the distance to pick up the medication and gave Jack his first dose that same evening.

The moment brought relief, but also frustration.

Drug shortage advocates say the situation was predictable. Because leucovorin is inexpensive and historically prone to shortages, any sudden increase in demand could easily disrupt supply.

Still, families continue to search for it.

The Working Mother’s Double Shift: Office Deadlines, Baby Duties and Endless Guilt | Women’s Day Special

Credit: Canva

Imagine standing at the starting line of a race, dressed properly with the best running shoes and ready to give your best. Yet, as the race begins, you notice that while half of the runners beside you have a clear path ahead, yours is filled with obstacles -- a dirty diaper, a crying baby, piles of laundry, a sink full of dishes, an empty fridge, cooking to be done, and countless other responsibilities.

If you pictured that correctly, you have just imagined the race of a man (with a clear road) and a woman’s race — more precisely, the race of a mother.

In 2019, the chairman of the Mahindra Group, Anand Mahindra, famously posted on the social media platform X, featuring the race of a working man and a woman, sparking a conversation on gender equality.

On International Women’s Day, women are given flowers, cake, or chocolates as a matter of appreciation for their seemingly multi-talented roles, but hardly does that go into consideration by families, partners, and workplaces.

Sanjana (name changed), a marketing professional from Bengaluru, was overjoyed as she held her first baby after a bout of four years of trying, several treatments, and constant pressure from family and society.

Speaking to HealthandMe, she said that the joy, however, was short-lived when she decided to get back to work.

“I had to figure out the support system -- what will I do, what will my husband do, and from what time to what time I need to keep a nanny. When I joined, I realized there was zero flexibility. I couldn’t leave work before completing a nine-hour shift and had to travel two hours back and forth. I was exhausted by the time I got back home, but nothing was ever ready for me to relax. It felt like the beginning of another shift after getting home.

"The baby would be eagerly awaiting me, and my mother's guilt was at its peak, so even though I was physically exhausted, I would still want to give him my time. Since I could never pick my baby up or get him or his meals ready for daycare, I felt guilty asking my husband to do more,” she told HealthandMe.

Shopping for groceries, refilling the baby’s necessities, making sure food is cooked as per everyone’s taste, and ensuring the baby’s routine isn’t disturbed are major responsibilities of most mothers.

“For a new-age mother, every day is a battle between love and responsibility. She meets deadlines with sleepless eyes and hugs her child with a tired heart. Judged at work, questioned at home -- yet she shows up. Not perfect, not rested, but relentless,” said Shivangi (name changed), an IT professional from Delhi.

While a woman’s quiet strength is often marked as victory, facing warzone-like situations every day -- from boardrooms to bedtime stories, meeting deadlines and doctor visits, balancing ambition, and affection -- takes a heavy toll on her mental and physical health.

HealthandMe spoke to Mimansa Singh Tanwar, Clinical Psychologist and Head of the Fortis School Mental Health Program at Fortis Healthcare, on the struggles of new mothers.

“New mothers often find themselves stretched thin while balancing the constant nurturing needs of the child and trying to realign their life with a change in their self-identity. This is a period of huge transition, both emotionally and physically, where new mothers tend to experience feelings of guilt for not being able to do enough for the child or not doing it the ‘right’ way. They often find themselves divided between work and the child’s needs once they resume work. It’s important to be gentle with yourself and accept that you don’t have to do everything perfectly,” Tanwar said.

“Being a mother is itself a moment of pure joy, but for many new mothers, it is also the beginning of a relentless balancing act. There are significant underlying hormonal and neurochemical changes that affect mood and behavior. Sleepless nights, multiple feeding schedules, household expectations, multitasking, and trying to match the ‘ideal perfect mother’ image can have a significant impact on the mind.

"Mothers often put their own needs quietly at the bottom of the list, which affects their overall well-being,” Dr. Sameer Malhotra, Principal Director - Department of Mental Health and Behavioral Sciences, Max Super Specialty Hospital, Saket, told HealthandMe.

Is There a Motherhood Penalty?

Several studies have pointed out how returning to the workplace as a new mother can be a vulnerable time for women. Many are likely to face baby blues, characterized by feeling weepy or anxious. Maternal labor force participation also sees a dip after motherhood.

A 2021 study published in the Journal of Development Economics showed that motherhood caused a sharp decline in employment in Chile, with 38 percent of working women leaving the workforce and 37 percent still out a decade later.

Global estimates by UN Women and the International Labor Organization (ILO) showed that more than 2 million mothers left the labor force in 2020.

During the pandemic, about 113 million women aged 25–54 with partners and small children were out of the workforce in 2020. This figure is astonishing, particularly when compared to their male peers (13 million of whom were out of the workforce, up from 8 million before COVID-19).

A 2007 study published in the American Journal of Sociology found that mothers face penalties in hiring, starting salaries, and perceived competence, while fathers can benefit from being a parent. Mothers were six times less likely than childless women and 3.35 times less likely than childless men to be recommended for hire. Mothers were also recommended a 7.9 percent lower starting salary than non-mothers.

How Mothers Can Help Themselves

Tanwar urged women to “be gentle with yourself and accept that you don’t have to do everything perfectly.”

Other measures include:

- Setting small, realistic goals

- Resting whenever possible

- Asking for help

- Sharing responsibilities with family members

- Staying connected with supportive family or friends

- Talking openly about your feelings to ease the load

“Simple self-care, even a few quiet moments each day, helps restore calm and energy. It is important to remember that looking after yourself is a key part of caring well for your baby,” Tanwar said.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited