- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

How Long After a Tattoo or Piercing Can I Donate Blood?

Credits: Canva

Are you that kind of person who celebrates milestones of your life with getting a tattoo? These milestones could be anything, including the things you achieved, or the things you could not achieve but taught you a lesson. If you are this person, then you must have wondered if you can donate blood with all the tattoos on your body? There are lots of rumors on how can one donate blood, or if at all they are allowed to donate blood. So let's get into its nitty gritty!

As per American Red Cross, in most states, a tattoo is acceptable if the tattoo was applied by a state-regulated entity. Which means the tattoo artist must be licensed and must practice following all the guidelines, using sterile needles and ink that is not reused. The same is the guideline for cosmetic tattoos, which includes microblading of eyebrows. If it is done by a licensed artist in a regulated state, then it is acceptable.

However, if you got your tattoo in a state that does not regulate tattoo facilities, you must wait three months after it was applied.

The states that do not regulate tattoo facilities are:

- Arizona

- District of Columbia

- Georgia

- Idaho

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New York

- Pennsylvania

- Utah

- Wyoming

Body Piercing

Similar is the case with body piercings. It has to be done following the regulation, here the key is that the instrument used has to be a single-use equipment and disposable. Which means if you are getting it by a gun, or an earring cassette, they have to be disposable. In case you got your piercing with a reusable gun or a reusable instrument, you will be required to wait for three months.

Three-Month Wait Period

The reason behind the wait time is associated with the concerns of hepatitis, which could be easily transmitted from donors to patients through transfusion. All blood donations are thus tested for hepatitis B and hepatitis C, with several tests. However, not always are these tests are perfect, thus the three-month period is given.

What Dangers Loom Over?

Donating blood after getting a tattoo can be dangerous as unclean tattoo needle could carry bloodborne viruses, which are hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIV. In 2020, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) updated its guideline, making the wait time shorter from one year to three months. This is because if you contract a bloodborne illness, it could be detectable within the period of 3 months.

What else makes you ineligible to donate blood?

There are other reasons why you may not be allowed to donate blood. As per the American Red Cross, you are not allowed to donate blood if you have

- hepatitis B or C

- HIV

- Chagas disease, which is a parasitic infection that kissing bugs cause

- leishmaniasis, a parasitic infection that sand flies cause

- Cruetzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD), a rare disorder that leads to mental deterioration

- Ebola virus

- hemochromatosis, which means extreme build up of iron

- hemophilia

- jaundice

- sickle cell disease

As per the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Blood Bank, these conditions make you permanently ineligible from donating blood.

While there are certain conditions that makes your permanently ineligible, there are other conditions that makes you temporarily ineligible from donating blood. These include:

- If you have a bleeding condition, and have issues with your blood clotting

- If you have received transfusion from a person

- If you have cancer. Here, the eligibility depend son the type of cancer you have

- If you have recently underwent a dental or oral surgery. In such a case, you would have to wait for three days

- If you had a recent heart attack, heart surgery or angina. You must wait for 6 months

- If you are pregnant, you can only donate blood after 6 months after delivering your child

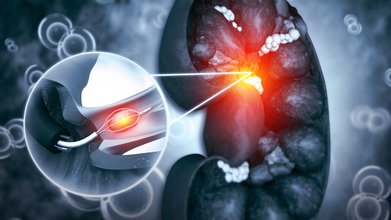

Study shows nanoparticles may shorten kidney stone laser surgeries, reduce recurrence

Credit: iStock

A team of researchers in the US has developed a nanoparticle-based technique that could make laser surgeries for kidney stones faster, safer, and potentially reduce the chances of recurrence.

Engineers from the University of Chicago and doctors from Duke University added dark nanoparticles to a common saline solution used in kidney stone laser surgeries. Their method also promised less recurrence of disease.

The research focused on laser lithotripsy, a widely used surgical method in which lasers are used to break kidney or urinary tract stones into tiny fragments that can then be removed by suctioning or pass naturally.

How Nanofluid Boosts Lasery Surgery

Traditionally, surgeons use a small video-guided laser to fragment the stones. However, achieving effective fragmentation often requires higher laser power, which generates additional heat and causes damage to the surrounding tissues.

Thus the new method “is a way to better utilize the laser energy that is already being employed,” said Po-Chun Hsu, assistant professor at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (UChicago PME).

Hsu noted that their nanoparticle-based “nanofluid” also has the potential to enhance the performance of lasers without increasing power levels. This will effectively fragment the stones and remove the dust particles.

The study, published in the journal Advanced Science, describes an innovative saline solution that enhances the performance of existing laser systems without requiring modifications to the equipment.

By adding dark nanoparticles that absorb laser wavelengths, the solution ensures that more of the laser energy is directed at the kidney stone rather than being reflected or dispersed.

“This improves the amount of laser energy that is transmitted to and absorbed by the stones,” said corresponding author Pei Zhong, a professor of engineering at Duke University.

“Nanofluid introduces a new dimension that can influence this complex physical process, independent of the stone composition or the laser being used,” Zhong said.

Kidney Stone Laser Surgery In 10 Minutes

Laboratory tests using artificial kidney stones showed that the nanofluid increased stone ablation efficiency by between 38 and 727 percent in spot treatments and by 26 to 75 percent in scanning treatments.

The researchers also tested the nanoparticle solution on living cells for up to 24 hours and found it to be non-toxic and safe.

In clinical settings, however, exposure would be much shorter. Laser lithotripsy is typically an outpatient procedure lasting about 30 minutes. The researchers believe that improved laser absorption could reduce the procedure time to around 10 minutes.

“If surgeries take too long, waste heat from the laser can accumulate and cause more harm than the stone removal itself,” Hsu said.

Kidney Stones: Symptoms And Prevention

Kidney stones are hard mineral or acid salt deposits formed in the kidneys. It occurs due to concentrated urine, and causes intense, radiating back/side pain, nausea, and blood in urine.

Common causes include

- dehydration,

- diet,

- obesity,

- family history

- metabolic issues

- staying well-hydrated

- reducing sodium levels

- eating fewer oxalate-rich foods

- consuming sufficient calcium-rich foods

- increasing citrus intake.

Amy Carr, Former England Youth Player Dies At 35

Credits: Instagram

Former youth player of England, Amy Carr dies at the age of 35. England women's football team too paid tribute on her death. Carr was a former goalkeeper who played for England Under-17s and Under-19s. She was diagnosed with a brain tumor for a second time.

She was diagnosed in 2015 and raised more than £2,000 for charity by running the Dublin Marathon in 2024.

"We are heartbroken to hear that former England youth player Amy Carr has passed away aged 35," read a statement on the Lionesses' X account. "Amy, who was diagnosed with a second brain tumour in 2024, devoted her time to raising money for vital brain tumour research that could help others. She remains an inspiration to all."

Carr also played for Arsenal, Chelsea and Reading before she gained a football scholarship in the USA. Chelsea added on X: "We are saddened to learn of the passing of former Chelsea goalkeeper, Amy Carr. Our condolences are with Amy's friends and family at this time."

What Is Brain Tumor?

Before diving into the concept of a brain tumor, it is important to first understand what a tumor is. A tumor refers to an abnormal lump or mass that forms due to the uncontrolled growth of cells in the body.

tumors are broadly classified into two main categories:

- Benign

- Malignant

A benign tumor consists of normal cells that have grown excessively to form a lump. This overgrowth may result from something going wrong in the body, but the cells themselves are not cancerous. On the other hand, a malignant tumor is made up of abnormal cells that grow uncontrollably. These are cancerous cells, and their aggressive nature can lead to serious health issues.

A brain tumor is a condition in which abnormal cells develop within any part of the brain. Similar to tumors elsewhere in the body, brain tumors can also be benign (non-cancerous) or malignant (cancerous). The presence of a tumor in the brain can interfere with normal brain function, depending on its size, type, and location.

Our bodies possess a natural healing mechanism that is crucial for survival. This repair system is activated whenever there is damage from injury, radiation from the sun, or harmful chemicals in the environment. However, this process can occasionally go wrong. When it does, small clusters of cancerous cells may begin to form. In most cases, the immune system successfully detects and destroys these abnormal cells before they grow. But in rare instances, these cancerous cells evade immune detection and continue to grow, leading to the formation of tumors or cancers.

Such abnormal growths can occur anywhere in the body. When these growths are located in the brain or spinal cord, they are referred to as Central Nervous System (CNS) tumors.

India Is Home To 25% of the World’s Cervical Cancer Victim

Credits: Canva

India is home to 25 per cent of the world's annual count of cervical cancer fatalities. According to the World Health Organization GLOBOCAN report of 2022, India reports over 120,000 new cases with nearly 80,000 fatalities. This is the highest death-toll worldwide from cervical cancer each year.

In India, a new case is diagnosed every four minutes, and another woman dies approximately every seven minutes. Persistent infection with high-risk HPV strains, especially types 16 and 18, is the leading cause of cervical cancer. Meanwhile, studies show that even a single dose of the HPV vaccine can provide long-lasting, potentially lifelong protection.

To combat this, India launched a nationwide campaign to vaccinate young girl against the human papillomavirus (HPV). This is also the second most common cancer among women in the country. India kicked off the nationwide campaign on 28 February. Prime Minister Narendra Modi at Ajmer city in the western state of Rajasthan inaugurated this campaign. Vaccines were made available free-of-cost at government facilities to approximately 11.5 million girls aged 14 years across the country.

Currently, approximately one in every 50 girls born in India is expected to develop cervical cancer during her lifetime, and widespread vaccination is likely to reduce this risk significantly," said Partha Basu, Head, Early Detection, Prevention & Infections Branch at the International Agency for Research on Cancer.

What Is Cervical Cancer?

Cervical cancer develops in a women's cervix (uterus opening) due to abnormal cell growth, primarily caused by persistent HPV infection, a common infection that's passed through sexual contact.

When exposed to HPV, the body's immune system typically prevents the virus from causing damage however, in a small percentage of people, the virus can survive for years and pave the way for some cervical cells to become cancerous.

Treatment involves surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy, with early detection significantly improving outcomes, though it remains a major cancer in low-income countries Cervical cancer can also be prevented through vaccination and regular screening (Pap/HPV tests).

Symptoms Of Cervical Cancer

Cervical cancer has no symptoms in the early days and therefore, is hard to detect until it has spread. However, the early-stage symptoms include:

- Vaginal bleeding after sex

- Vaginal bleeding post-menopause

- Vaginal bleeding between periods or unusually heavy/long periods

- Watery vaginal discharge with a strong odor or containing blood

- Pelvic pain or pain during intercourse

- Advanced Cervical Cancer Symptoms (when cancer has spread beyond the cervix)

- Painful or difficult bowel movements or rectal bleeding

- Painful or difficult urination or blood in the urine

- Persistent dull backache

- Swelling of the legs

- Pain in the pelvis or lower abdomen

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited