- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

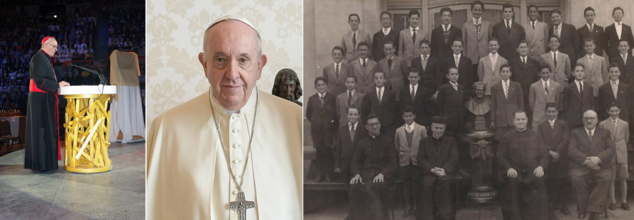

Pope Francis Passes At 88, After Battling A Long-Term Health Crisis

Credits: Wikimedia Commons

Pope Francis, the 266th pontiff of the Roman Catholic Church passed away at the age of 88. The Vatican confirmed his passing on Easter Monday, on April 21, 2025, at Casa Santa Marta, his long-time residence in Vatican City.

Cardinal Kevin Farrell in the statement published by the Vatican on its Telegram channel said: "This morning at 7:35 am (0535 GMT) the Bishop of Rome, Francis, returned to the home of the Father."

His death has come just after a month he was discharged from a hospital stay for double pneumonia. This was the latest in string of health challenges that marked his later years.

The Series of Illness and Recovery

Francis, born Jorge Mario Bergoglio in Buenos Aires, Argentina, had battled numerous health issues over the course of his life. His final hospitalization began on February 14. He was admitted to Rome's Agostino Gemelli Polyclinic Hospital. He was diagnosed with bronchitis and his condition worsened and developed into double pneumonia. After 38 days of treatment, he was finally discharged on March 23. However, he passed away a few weeks later.

On the day he was discharged, Archbishop Edgar Peña Parra, the Vatican's chief of staff, visited the pope multiple times during his hospitalization and expressed optimism about his recover. “The pope will recover. The doctors say that he needs some time, but it’s going well progressively,” Peña Parra said.

He earlier showed signs of improvement, however, even then, his recovery was not without its challenges. The Vatican also confirmed that he required rehabilitation therapy to regain his strength, especially when it came to his ability to speak after weeks of using noninvasive mechanical ventilation.

The Vatican also had periodically released health updates, including an audio message recorded from hi hospital bed on March 6. In it, the Pope also thanked people for their prayers and asked for the Virgin Mary's protection. While he was hospitalized, he marked the 12th anniversary of his papacy on March 13. This went along with a quiet celebration and his staff brought him a birthday cake.

However, Pope Francis had a long history of respiratory problems. At 21, he also had a near-death experience from a severe bout of influenza that resulted in part of one lung being removed. This, for him was a life altering experience, he later described in his book Let Us Dream. "for months, I did not know who I was, and whether I would live or die," he wrote, calling it his first real encounter with pain and loneliness.

In June 2021, he underwent colon surgery, and throughout COVID-19 pandemic, he remained cautious, often curbing public engagements. Despite all such setbacks, he kept a demanding schedule well into his 80s.

A Legacy Of Compassion To Continue

Despite his age and ailments, he remained active until the very end. Just a day before his death, he met with the US Vice President JD Vance. On Easter Sunday, while he was too frail to deliver the tradition "Urbi et Orbi" blessing himself, he made a passionate plea through a delegated speech for "freedom of religion, thought, and expression” and condemned rising anti-Semitism and the crisis in Gaza.

Previous updates on Pope Francis' Health, Find Here.

CDC Notes A Remarkable Drop In Drug Overdose Deaths

Credits: Canva

A surprising, but encouraging turn takes place in the United States as drug overdose deaths show a dramatic decline. This is based on the new provisional data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), that showed that these cases have plummeted by nearly 30% in 2024 as compared to in 2023.

The National Center for Health Statistics also estimated a 27% drop from 110,037 deaths in 2023 to 80,391 in 2024. This has marked the lowest total since 2019.

This significant drop, while still based on the provisional data that could differ from the final count does offer a hopeful sign in the long battle against an epidemic that has claimed as many as more than 1 million lives since 1999. This also remains to be the leading cause of deaths for Americans aged 18 to 44.

Efforts And Strategies

Health experts and CDC officials have attributed this decline to years of targeted federal investment and enhanced data systems. In fact, President Donald Trump also declared the opioid crisis a public health emergency in 2017. Furthermore, the Congress also funded expanded CDC programs that now help states to collect real-time overdose data.

In fact, recently, the US Health Secretary Robert F Kennedy Jr also opened up about his own battle with drug addiction and his journey to recovery.

“These investments have empowered us to rapidly collect, analyze, and share actionable data,” the CDC said in a statement. “Since late 2023, overdose deaths have steadily declined each month — a strong sign that public health interventions are making a difference.”

Where Does The Most Decline Account For?

Much of the overall decrease is driven by fewer deaths from fentanyl and other opioids.

As per the United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), fentanyl is a potent synthetic opioid drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use as an analgesic (pain relief) and anesthetic, based on prescription. It is approximately 100 times more potent than morphine and 50 times more potent than heroin as an analgesic. It is also known as China Girl, China Town, Murder 8, Poison and Tango & Cash as its street name.

It is consumed by snorting, sniffing, smoking, orally by a pill or tablet, or spiked onto blotter paper and patches.

The DEA notes that overdose can cause stupor, changes in pupil size, clammy skin, cyanosis, coma, and respiratory failure leading to death.

Fentanyl-related deaths fell by nearly 37%, from 76,282 in 2023 to 48,422 in 2024. Deaths involving any type of opioid also dropped significantly — down from 83,140 to 54,743.

Other drugs showed similar trends. Cocaine overdose deaths decreased from an estimated 30,833 to 22,174. Psychostimulant-related deaths, including those from methamphetamine, declined by 20%, from 37,096 to 29,456.

Data From States

Nearly all states showed progress. States such as Louisiana, Michigan, New Hampshire, Ohio, Virginia, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and the District of Columbia posted the most dramatic single-year declines each over 35%.

Only two states bucked the trend. Nevada saw a 3.5% rise in overdose deaths, while South Dakota reported a 2.3% increase.

Experts point to a variety of factors. Dr. Stephen Taylor, president of the American Society of Addiction Medicine, credits greater access to addiction treatment services and wider availability of naloxone, a drug that reverses overdoses.

“I think the most important issue has been the expanded access to care,” Taylor said. However, he warns that proposed cuts — such as Trump’s suggested $1 billion reduction in funding to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration — could threaten the progress made.

Dr. Daniel Ciccarone, a researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, believes fewer new people becoming addicted may also play a key role. “Epidemics come to an end because the number of new people entering the drug scene drops below the number exiting — whether through recovery, treatment, or sadly, death,” he said to US News.

India Underreported Nearly 20 Lakh Excess Covid Deaths In 2021- Was Death Toll Really 6X Higher?

Credits: iStock

The second wave of Covid-19 in India was not just a crisis, it was a tragedy experienced in all corners of India. When oxygen supplies in hospitals ran out and funeral pyres were lit throughout the day and night, it was clear for everyone to see and feel how vast the devastation was. Family members lost dear ones within days, even hours. Yet, as dire as the situation appeared, recently published government statistics from India verify what many suspected- the actual death count was much worse. The official count of Covid deaths in 2021 was 3.3 lakh but the true excess deaths that year exceeded 20 lakh. That's almost six times greater than reported. The shocking gap indicates a trend of underreporting, bureaucratic obscurity, and political evasion, evoking international concern regarding transparency and accountability in pandemic governance.

India reported more than 1.02 crore deaths in 2021 — a whopping rise of almost 21 lakh from the last year — as per latest figures made public by India's Office of the Registrar General. In 2020, 81.2 lakh deaths were registered, and in 2019, the figure was 76.4 lakh. The surge in death, at the height of the second wave of the pandemic, sends red lights flashing immediately. Though not every one of these deaths can be attributed to Covid-19, the timing and the circumstances imply the virus contributed heavily, underreported.

Three official data sets — Sample Registration System (SRS), Civil Registration System (CRS), and Medical Certification of Cause of Death (MCCD) — were employed to assess trends in mortality. Of the three, CRS continues to be the most complete source, and it irrefutably indicates a record spike in deaths in 2021. All this is not only crucial for the realization of the pandemic's actual burden but also provides a prism into India's death registration and certification system failures.

Why the Official Covid Death Figures Don’t Add Up

The Union Ministry of Health had pegged the total number of Covid-19 deaths in 2021 at 3.3 lakh. However, the MCCD report, based on medically certified deaths, listed 4.13 lakh Covid-related fatalities. That alone suggests a significant gap. But here’s the critical twist: the MCCD data only covers 24 lakh deaths — just 23% of all deaths registered that year.

This difference suggests that there may not have been medical certification of numerous Covid-19 deaths, either because the healthcare infrastructure was burdened or because of systemic failure in certifying causes of death. Even among that smaller dataset, Covid-19 deaths exceeded the Health Ministry's figure, directly indicating official undercounting.

Maybe the most stark evidence of underreporting is from Gujarat. The BJP-ruled state had reported just 5,812 Covid deaths in 2021. But the actual number of deaths registered through CRS was 1.95 lakh — more than 33 times greater. Independent calculations by Kerala-based volunteer Krishna Prasad's dashboard reported that Gujarat had more than 2 lakh excess deaths that year.

Madhya Pradesh and West Bengal also had the same trends, with huge discrepancies between Covid-19 death claims and the actual amount of excess mortality. Madhya Pradesh had reported 6,927 official Covid deaths but had an excess of almost 2 lakh deaths over 2020. Uttar Pradesh, the most populous state of India, had an excess of 4.78 lakh deaths in 2021 when just 22,918 were officially claimed due to Covid-19. Kerala was an exception to the trend, having relatively more accurate death statistics.

What's Behind India's Spike in Crude Death Rate

Statisticians also reference the crude death rate, deaths per 1,000, as another insightful metric. From a consistent rate of 6 in both 2019 and 2020, it surged to 7.5 in 2021. This increase is not random; it reflects an abnormal spike in mortality concurrent with the pandemic peak.

If India's crude death rate of 6 in the historical years continued to 2021, the estimated deaths would have been approximately 82 lakh, consistent with previous years. The increased crude death rate in 2021 aligns with the 1.02 crore reported deaths very closely, implying over 20 lakh excess deaths, which cannot be accounted for by better registration.

In April 2022, the World Health Organization put India's estimated Covid-19 toll in 2020 and 2021 at 47 lakh deaths, either directly or indirectly due to the pandemic — eight-and-a-half times the number reported officially. India's government had dismissed the WHO report for being inappropriate in methodology for a country of the size of India. But interestingly enough, the very Registrar General of India whose figures have been quoted by the government is now lending strength to the suspicion of large-scale undercounting.

The contrast is stark: India dismissed international models as speculative, but its own official statistics now confirm excess deaths in line with WHO estimates. This is a matter of profound concern regarding data suppression, political motive, and the right of citizens and the international health community to the truth.

Why Accurate Data Matters?

Mortality data accurately gathered matters more than numbers. It affects how nations prepare for pandemics, how resources are allocated to healthcare, and how people have faith in public institutions. For India, the world health leader and manufacturer of vaccines, poor data transparency erodes credibility and undermines global cooperation in public health.

Additionally, for the uncounted families many of whom were denied medical care, social acceptance, and economic ruin, the government silence is another injustice. Without official acknowledgment, they're typically not given government compensation, aid, or even recognition.

The information is now out presenting how India saw a mortality spike in 2021 that is more than six times bigger than its official Covid-19 death toll. It matters little whether the cause is deliberate cover-up or systemic failure- the result is the same- the lives lost in secrecy amount to millions.

Going forward, India has to build stronger health data infrastructure, conduct independent audits, and uphold transparency. The world witnessed the funeral pyres burn and now, the figures finally tell us the unthinkable truth many had suspected all along.

Parkinson’s Disease May Have A New Environmental Trigger- Can It Be Avoided?

When we consider health risks, we tend to look inward—diet, lifestyle, genetics but what if the biggest threats come from what’s around us? Environmental causes have increasingly been in the primary concern of health studies, with connections being found between pollution in the air and respiratory disease, industrial toxins and cancer, and now perhaps even our most idyllic, verdant neighborhoods. According to a new research, just being close to a golf course may be linked with a much greater risk of acquiring Parkinson's disease.

Yes, golf courses—those enormous, manicured landscapes we commonly think of as tranquility and recreational—might be more poisonous than they seem. The report, which appeared online in JAMA Network Open, sends significant concern about the long-term effects of environmental pesticide exposure on these greens, particularly for those who live nearby. Although far from definitive, the results add fuel to a growing controversy: Might our seemingly picture-perfect environments be quietly undermining brain function?

A research team headed by Brittany Krzyzanowski from the Barrow Neurological Institute investigated whether proximity to golf courses in one's neighborhood could potentially be associated with Parkinson's disease—a chronic neurological condition for which there is currently no cure. Based on a population-based case-control study comprising 419 patients with diagnosed Parkinson's and 5,113 healthy controls across different regions in the US, the researchers found something disturbing- Living in one mile of a golf course was linked with a 126% higher risk of Parkinson's disease compared to those residing more than six miles away.

Additionally, residents of areas where water services encompassed golf course areas had almost double the risk of Parkinson's versus those residing in golf-free areas. These correlations persisted even after controlling for neighborhood and demographic variables.

What Is It About Living Close to Golf Course That's a Red Flag for Your Health?

The research doesn't say golf courses cause Parkinson's directly—but it does propose a compelling hypothesis. The suspected perpetrators are pesticides, which are applied freely to keep golf courses looking nice. The chemicals, frequently airborne or leached into water, might end up being inhaled or ingested by nearby residents.

This hypothesis is not new. Past research has indicated a greater prevalence of Parkinson's in farmers, field workers, and residents of industrial areas. Some lab research has demonstrated that some pesticides and air pollutants are harmful to dopaminergic neurons, the very same cells that in Parkinson's disease.

The new evidence supports the hypothesis that long-term, low-dose exposure to neurotoxic chemicals—particularly by air and water—may play a causative role in causing the illness. But experts caution against overinterpretation.

Not everyone in the scientific community is convinced. Parkinson’s UK, a leading non-profit that supports neurological research, has expressed skepticism about the study's conclusions. Katherine Fletcher, a lead researcher with the organization, notes that while many studies have examined links between pesticide exposure and Parkinson’s, the evidence remains inconclusive.

"Effects have been inconsistent, but in general point toward pesticide exposure possibly elevating risk," Fletcher replies. "The evidence, though, is not as strong to conclude that exposure to pesticides is directly causing Parkinson's."

David Dexter, another Parkinson's UK expert, questions methodology. The study didn't check for true contamination of air or water around the golf courses. Nor did it take into account other possible sources of pollution, such as traffic emissions, that might have an effect on neurological health.

Why it is Important to Rethink Where We Live?

What's most unnerving is the way seemingly wholesome, affluent neighborhoods might harbor hidden health threats. Environmental exposure and disease clusters aren't new. But in contrast to industrial complexes, golf courses are frequently situated in upscale areas, promoted as serene and picturesque.

This paradox makes the new study more intriguing—and more contentious. Although it doesn't have answers, it raises an immediate question: Are we reconsidering the safety of our environment?

Can This Risk of Parkinson's Be Avoided?

For now, there’s no need to panic or sell your home next to the 18th hole. The findings call for further investigation, not alarm. Krzyzanowski and her team argue that public health policies aimed at reducing pesticide use on golf courses could be a step in the right direction. This could include:

- Switching to eco-friendly turf management practices

- Enforcing stricter groundwater monitoring regulations

- Increasing transparency around chemical use in residential areas

Finally, until more conclusive studies, prevention is paramount. If you're near a golf course—or anywhere with intensive pesticide application—it may be a good idea to take note of local water quality summaries and air quality indices.

This research is not the last word on Parkinson's and golf courses—but it begins an essential dialogue. As we swim through the rising tide of diseases caused by the environment, it's more and more apparent that health is not solely the result of genes and behaviors. It's also strongly connected to place.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited