Credits: Canva

Flu Shot Linked To Higher Risk Of Infection This Year, Study Raises Eyebrows- Should You Be Concerned?

This flu season has turned out to be quite a surprise. A new study from Cleveland Clinic indicates the 2024–2025 flu shot might have fallen short — and potentially worsened the situation. With vaccinated patients reportedly having higher infection rates, health professionals and the general public are now reassessing the vaccine's effectiveness in real life.

New research from the Cleveland Clinic has caused alarm among health professionals and the general public. In contrast to years of conventional wisdom, the current flu shot may not only have been useless — it could actually have made some people more susceptible to the flu.

Released as a preprint on MedRxiv.org, the Cleveland Clinic study compared infection rates among more than 53,000 of its own staff and concluded that vaccinated staff had a higher rate of flu infections than their unvaccinated peers. Although the study is not yet subject to peer review, early conclusions have sparked a firestorm of questions about vaccine effectiveness, public health policy, and efforts to prevent future influenza.

Carried out across 25 weeks of the 2024-2025 respiratory viral season, the study monitored flu infection rates among Cleveland Clinic staff — predominantly a cohort of healthy adults of working age.

- Vaccinated staff had a 27% higher rate of flu infections than the unvaccinated cohort.

- Effectiveness of the vaccine was estimated at -26.9%, reflecting not only diminished protection, but a seeming increase in risk.

- The rate of influenza initially tracked similarly in both groups, but increased more steeply in the vaccinated as the season went on.

Notably, almost 99% of the vaccinated workers got the trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine, so it is difficult to know whether other formulations of the vaccine might have produced different results.

What Does "Negative Vaccine Effectiveness" Really Mean?

Negative vaccine effectiveness — particularly in the range of -26.9% — is a dramatic and disconcerting statistic. Yet, it does not indicate the vaccine induces the flu. Rather, it suggests that in this specific season, the vaccine provided no significant protection and potentially was not well matched to the prevailing virus strains.

The Cleveland Clinic explained in a statement to Fox News Digital, "The results do not suggest that vaccination increases the risk of flu. Instead, the study implies that the effectiveness of this season's vaccine in preventing influenza may have been limited in relatively healthy healthcare workers."

That is to say, the virus could have caught up with the shot.

While the results are surprising, specialists point out that this study is far from being the last word regarding the effectiveness of flu shots. There were several limitations the authors have acknowledged:

The research did not test flu severity of symptoms, hospitalizations, or fatalities — which are important indicators of vaccine worth.

It tested only healthcare workers, but not children, elderly people, and immunocompromised individuals, who most usually benefit from flu vaccination.

The vast majority of participants were given one type of vaccine, so the performance of others remains unknown.

Dependence on home test kits could have resulted in underreporting or misclassification of certain cases.

Why the Flu Shot Works Differently Each Year?

Performance of flu vaccines differs from year to year because of a number of factors:

Strain Mismatch: Every year, vaccine manufacturers make an educated estimate of the most common flu strains. If they're incorrect, the vaccine will provide suboptimal protection.

Population Immunity: Immune response varies with age, health, and past experience with flu viruses or vaccines.

Mutation Rates: Flu viruses change rapidly. Even when production starts, strains can change, lowering efficacy.

This year could just have been an anomaly in terms of immune response or strain drift — but the stakes are high for how we handle flu vaccination in the future.

Physicians warn not to make quick judgments based on a single preprint study. Dr. [Name], infectious disease physician at [Institution], cautions:

While Cleveland Clinic research is definitely worth further examination, it's important to keep in mind that the flu vaccine's greatest aim is to curb severe illness and mortality. We just don't have enough data yet to realize the total effect of this year's vaccine.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) still encourages yearly flu vaccination for all people six months and older based on long-standing proof that flu vaccinations decrease the possibility of serious complications from the flu.

Should You Still Get the Flu Shot?

The quick answer: Yes — but with awareness.

This study points out that flu vaccine effectiveness can vary, and in extreme cases, may even not protect as expected. But overall evidence still continues to affirm the vaccine's function of reducing hospitalizations, decreasing duration of illness, and safeguarding high-risk groups.

If anything, the results emphasize the importance of ongoing investment in the development of vaccines, improved real-time surveillance of viral mutations, and open reporting of vaccine performance.

The Cleveland Clinic study doesn't mark the end of the flu shot — but it does pose important questions about how we produce, test, and present vaccine effectiveness. As more evidence comes in and peer-reviewed evaluation is finalized, health authorities will most likely fine-tune their approach to prevent future flu seasons from catching us unprepared.

RFK Jr.'s Autism Controversial Comments Face Backlash From Parents And Medical Experts

Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services, is facing strong backlash after making sweeping comments during a recent press conference regarding autism and its supposed causes. As the CDC released a report revealing a rise in autism diagnoses among U.S. children now affecting 1 in 31 8-year-olds Kennedy doubled down on discredited theories linking autism to environmental exposures and vaccines, while portraying the disorder in stark, stigmatizing terms.

His remarks including claims that children with autism “will never hold a job,” “never pay taxes,” or “never use a toilet unassisted”, were swiftly condemned by parents, medical experts, and advocacy groups alike for reinforcing outdated stereotypes and misrepresenting the broad and diverse autism spectrum.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is not a single condition with uniform symptoms or outcomes. Rather, it is a neurological and developmental condition characterized by challenges in social interaction, communication, and repetitive behaviors. The key word is "spectrum" and it exists for a reason.

Some individuals with autism may be nonverbal and need lifelong support, while others live independently, excel in careers, write books, or even hold public office. “Autism is not a disease,” said actress and autism advocate Holly Robinson Peete in a video statement, responding to Kennedy. “It is a developmental difference and it is important to get that right.”

Her son, RJ, diagnosed 25 years ago, has “shattered a lot of 'never' off that list,” she said, referring to Kennedy’s grim portrayal. Countless parents echoed this sentiment on social media, stating that Kennedy’s generalizations erase the lived realities, milestones, and accomplishments of their children.

CDC Data Shows a Rise in Diagnoses

The CDC’s Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network reported that 1 in 31 8-year-olds in the U.S. were diagnosed with autism in 2022, compared to 1 in 54 in 2016. But experts stress that this increase is not necessarily cause for alarm. It is, in fact, a sign of progress.

The rise in autism rates is driven largely by improved awareness, broader diagnostic criteria, and increased access to evaluations and services. We are identifying children earlier and more accurately that’s a good thing.

Kennedy, however, rejected this explanation as “indefensible” and announced plans for a directive to the National Institutes of Health to investigate “environmental exposures” as the root cause — reigniting long-debunked concerns about vaccines and toxins.

Despite overwhelming scientific consensus debunking any link between vaccines and autism, Kennedy has long been associated with promoting vaccine hesitancy. His latest comments, veiled in language about “environmental exposures,” once again hint at this discredited narrative.

Leading medical organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics and the World Health Organization, have repeatedly emphasized that vaccines are safe, effective, and have no causal relationship with autism. Resurrecting these claims only spreads fear and confusion. It undermines public health and harms autistic people by framing their existence as a preventable tragedy.

Parents Demand a Shift in the Narrative

Perhaps the strongest rebuke came from parents of autistic children themselves. Samantha Taylor, whose 20-year-old son is on the spectrum, told Good Morning America, “Autism doesn’t destroy families misinformation does.” In a viral Facebook post, she added, “What truly causes damage is the relentless portrayal of autism as something catastrophic, rather than a different way of experiencing the world.”

Kennedy’s comments, they say, not only ignore the complexity of the condition but strip children of their dignity and potential.

“Statements like ‘they’ll never write a poem’ deny the creative genius that so many autistic individuals demonstrate,” said Peete. “It’s dangerous, it’s harmful, and it’s simply false.”

Experts Call for More Informed Leadership

While Kennedy has promised answers by September through federally backed studies, medical experts warn that his rhetoric may set back years of advocacy and research by framing autism as an “epidemic” akin to an infectious disease.

Autism is not something to be eradicated, it’s something to be understood, supported, and embraced. Families deserve resources, not fearmongering.

In the last two decades, the medical community has shifted toward neurodiversity — a perspective that recognizes neurological differences like autism as natural variations of the human genome. This philosophy emphasizes inclusivity, respect, and strength-based approaches rather than medicalizing difference.

At a time when public trust in institutions is fragile, the words of public officials matter deeply. Kennedy’s comments have triggered a reckoning not only about how autism is portrayed in the media and politics but also about how society chooses to value — or devalue — people who are different.

Advocates stress the need for policies rooted in science, not stigma, and for leadership that uplifts rather than marginalizes.

As the national conversation around autism continues, one thing is clear: the autism community — parents, children, adults on the spectrum, clinicians, and allies — is not going to stay silent in the face of outdated narratives.

Credits: Canva

World Liver Day: How A Timely Liver Transplant Saved A 30-Year-Old Man

On World Liver Day, which is observed on April 19, to spread awareness about liver health and the life-saving power of organ donation, let us look at one such real-life story. This is where doctor's prompt's action and one's selfless donation saved one human's life.

When the 30-year-old Delhi-based man walked into the hospital, he had yellow eyes and dangerously high liver enzymes. He was admitted in Max Super Speciality Hospital, Patparganj. That moment, he rarely knew that his life was, in fact, hanging by a thread. The man was diagnosed with acute liver failure, which was caused by viral hepatitis. His body was slowly shutting down. The frequency of his body shutting down had increased. The doctors also quickly informed the family. This was the one last hope of survival - a liver transplant.

The First Option Failed

His sister was family's first ray of hope. She was also willing and had a compatible liver whose part of it could be donated. However, pre-surgery tests revealed that her liver size was too small to ensure a safe transplant. The family then proposed the patient's brother-in-law - a second-degree relative, as the next donor. His liver was a better match, but since he was not an immediate blood relative, there had to be special regulatory approvals which were required.

However, the worsening condition of the patients allowed no such time.

The hospital too scrambled to get clearance for the brother-in-law. All this while, the patient suffered a cardiac arrest. The situation turned dire within minutes. Doctors performed CPR to revive him. He was immediately put on ventilator support. The decision had to be taken soon.

A Miraculous Surgery

With no time in hand, the doctors decided to go ahead with the sister as the donor, though there were risks there too.

A team of highly skilled hepatobiliary surgeons, anesthesiologists, and critical care specialists took over. In a high-risk, nine-hour surgery, they removed the patient’s failing liver and replaced it with part of his sister’s.

“This was one of the most challenging cases we’ve handled,” said Dr. Ajitabh Srivastava, Director – HPB Surgery & Liver Transplant. “When the patient collapsed, our team acted within seconds. Every decision, every move mattered. His survival was truly a team triumph.”

The patient is now recovering well.

What Is A Liver Transplant?

As per the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, a liver transplant is a surgical procedure to replace a diseased liver with a healthy one from a donor. It’s often the last resort when liver failure occurs—whether due to chronic illness or sudden injury.

When Is It Needed?

People may need a liver transplant for:

- Alcoholic liver disease

- Fatty liver disease (NASH)

- Cirrhosis due to chronic hepatitis C

- Liver cancer with cirrhosis

- Acute liver failure (often due to drug overdose, hepatitis, or toxins)

Types of Liver Transplants

Deceased Donor Transplant:

The most common type, where a full or partial liver is taken from someone who has recently died.

Living Donor Transplant:

A healthy person donates a portion of their liver—typically a close relative. Both the donor’s and recipient’s liver regenerate to normal size in a few weeks.

What Must Be Kept In The Mind?

- Matching and Compatibility: Blood type, liver size, and health are crucial.

- Approval Process: Especially important for non-blood relatives.

- Recovery and Monitoring: Post-op care involves lifelong medication, lifestyle changes, and regular check-ups.

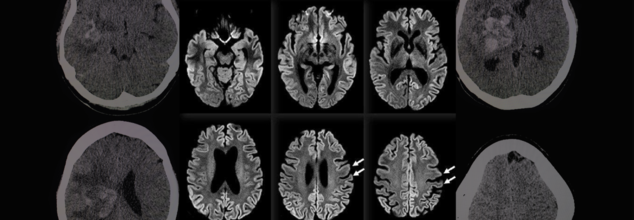

Rare 100% Deadly Brain Disease Kills Two In Oregon County, Third Infection Confirmed

A rare and fatal brain disease with a 100% mortality rate has gripped Hood River County, Oregon, raising concerns within the medical community and eliciting intense probes by local and federal health officials. It is called Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD), and it has killed two people and impacted a third in eight months—a terrifying cluster in a county of only slightly more than 23,000 people.

On April 14, the Hood River County Health Department reported one case of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease and two more probable cases. Although only one case has been confirmed by a diagnosis through an autopsy, the other two are presumptive and await post-mortem confirmation through examination of brain tissue and cerebrospinal fluid. Such examination, as explained by Trish Elliott, Director of the Hood River County Health Department, may take months.

Although the origins of these three cases are still unknown, the cluster is epidemiologically significant. The U.S. experiences about 350 cases of CJD each year, or 1 to 2 cases per million individuals globally. For Hood River County, with only 23,000 people, to see three cases over such a brief time span is an epidemiologic outlier.

What Is Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD)?

Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease is a rapidly advancing and always lethal neurodegenerative disease resulting from misfolded proteins known as prions. Initially documented in the 1920s by German physicians Hans Gerhard Creutzfeldt and Alfons Jakob, CJD causes sponge-like holes to form within the brain, destroying its structure and function.

CJD is a member of the larger family of prion diseases, which also encompasses other rare but fatal disorders like kuru and fatal familial insomnia. Similar to bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), commonly referred to as mad cow disease, CJD irreversibly destroys the brain and has no cure.

CJD Symptoms and Progression

The symptoms of CJD are extreme and worsen quickly. Early symptoms may involve confusion, disorientation, personality changes, memory loss, visual disturbances, and stiffness of the muscles. Later in the disease, patients can develop hallucinations, difficulty speaking or swallowing, seizures, and sudden jerky movements.

Death typically occurs within a year of the onset of symptoms, usually as a result of complications such as pneumonia, heart failure, or problems arising from neurological deterioration such as falls and choking.

Symptoms in the early stages of sporadic CJD usually resemble other dementias but worsen with terrifying rapidity. The majority of individuals with sporadic CJD are between 50 and 80 years of age, but some genetic forms can occur earlier, even in some people as young as 30.

Various Types of CJD

CJD comes in several types:

Sporadic CJD (sCJD): This type is the most prevalent, affecting about 85% of the cases. This type happens spontaneously when healthy proteins in the brain misfolded into prions for unknown reasons.

Genetic CJD (fCJD): Due to mutations in the PRNP gene, this form is inherited and represents about 10–15% of the total cases. The PRNP gene codes for the prion protein (PrP), a protein involved in neuronal communication and protection.

Acquired CJD (also referred to as iatrogenic or variant CJD): This is a rare type that involves outside sources of infection, such as eating infected beef (BSE/mad cow disease) or through tainted medical equipment or transplanted tissue.

In spite of concerns, authorities from Hood River County stressed that the present cases do not seem to have resulted from infected cows. "At this point in time, there is no cause identified between these three cases," the department noted. They also pointed out that CJD cannot be transmitted via air, touching, social contact, or water.

Public Health Measures and Continued Investigations

The Hood River County Health Department, in collaboration with the Oregon Health Authority and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), has launched an "active and ongoing investigation" into the three reported cases.

“We’re trying to look at any common risk factors that might link these cases,” Trish Elliott told The Oregonian. “But it’s pretty hard in some cases to come up with what the real cause is.”

Although risk to the general population is "extremely low," the health department continues to monitor it. Since CJD cannot be definitely diagnosed until after death, real-time monitoring is not easy, and so robust surveillance is essential.

Can CJD Be Prevented?

Although there is no treatment or cure to prevent the development of CJD, the U.S. has established strict public health measures to minimize the risk of acquired CJD, especially through food supply control and medical safety measures.

Federal authorities have maintained since the 1990s a prohibition against feeding cattle which could be contaminated with BSE, and employment of high-risk material in foods is strictly barred. Sterilization processes of surgical devices as well as strict donor screening in transplantation and transfusions are all undertaken to cut back on iatrogenic spread.

While medical officials wait for further verification and possible connections between the three patients, the attention is on education, surveillance, and reassurance to the public.

Although it is reassuringly ominous to witness a disease of this kind emerging in a small American community, the risk at the international level remains low, especially with measures presently in place. Nevertheless, the cases are a sobering reminder of the enigma that prion diseases continue to pose to modern medicine.

Health officials are still keeping an eye on the matter and are asking people not to panic but to remain updated. "The health department will remain vigilant and inform you of any public health risk," officials promised in a statement.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited