- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

- Web Stories

Flu Is A Greater Risk This Winter, Not COVID

It has been five years since the first case of COVID-19 was reported in the US, since then it has unleashed winter waves of illness. It is the mutation of the strain, and every winter, there was a new one. However, this winter, COVID seemed much more muted, the hospitalization rates to have gone down. While it is a good news for the people, bad news and diseases have lingered in form of flu.

This winter season walking pneumonia, RSV, norovirus and bird flu, along with influenza grabbed more attention than COVID-19.

Why Are These Diseases or Viruses More Active In Winters?

Winter offers to best condition for airborne viruses to spread because this is the season when people travel the most or gather due to the holidays. People also spend more time indoors, go out in the sun much less. As per Demetre Daskalakis, who directs the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)'s response to respiratory infectious-disease threats, "Right now, flu is the driver."

However, it is not easy to compare the previous winter COVID-19 waves with current cases as the data and its collection has changed. Hospitals no longer test every patient for covid, and official tallies are no longer available as more and more people are taking tests at home or not taking the test anymore. However, if one has to compare, it is best to rely on the CDC reports which notes that 38 out of every 100,000 people who were hospitalized this season had COVID-19, as of January 11. This is less than half the rate at the same point last year.

So, what changed this winter?

Unlike flu or RSV, COVID-19 stays even during the spring and in summer, and the COVID-19 wave this summer (2024) was worse than the one in 2023. This is why when winters arrived, it was much weaker, says Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist and director of the Pandemic Center at the Brown University School of Public Health, reports The Washington Post. “We had such a huge summer wave of infection, and that left in its wake a lot of immunity,” Nuzzo told the news outlet.

What this means is those who were exposed to COVID-19 in summer were less likely to become infected by the virus in the winters. While the virus has mutated, formed new strain, however, it has not evolved drastically.

When someone develops immunity against a virus due to vaccination, the virus then has to evolve to bypass the antibodies trained to block it to keep infecting people. While there has been accounts of the XEC variant, for half of the new cases, it is not necessarily very different from the KP and FLiRT strain.

“We are definitely moving in a very similar axis of viruses where there’s not been like a sudden shift or a change that evades immunity,” Daskalakis told The Washington Post.

However, having said that, it does not necessarily mean that by each winter, the virus will get weaker, because there is a fair chance for the virus to evolve and more threatening variants to emerge. This could affect people because while most Americans got their first COVID-19 shots, they were much less willing to get booster doses.

Credits: Canva

Kerala Reports New Nipah Virus Case As Woman Tests Positive; Know Fatal Symptoms Of This Zoonotic Infection?

A 42-year-old woman in Malappuram, Kerala, was admitted to a private hospital with severe symptoms resembling encephalitis. Just days later, her worst fears were confirmed — she had contracted the Nipah virus. On Thursday, the National Institute of Virology (NIV) in Pune officially verified the infection, thrusting Kerala once again into the national spotlight as it battles another outbreak of this deadly zoonotic disease.

As Health Minister Veena George heads to Malappuram to monitor the containment strategies, public health concerns are intensifying, especially given the virus’s history in the state and the high fatality rate associated with it. Here’s everything you need to know about the Nipah virus, how it spreads, and why it’s resurfacing now.

Kerala is no stranger to the Nipah virus. Since 2018, the state has witnessed five outbreaks, leading to 22 confirmed deaths. The first outbreak in 2018 was particularly catastrophic — 17 of the 18 infected individuals died, leaving public health systems scrambling for solutions. Further cases occurred in 2019, 2021, and 2023, most commonly between May and September, the region’s monsoon season, which is also marked by a surge in respiratory infections and influenza-like illnesses.

These seasonal overlaps make early diagnosis challenging, as Nipah symptoms often mimic more common illnesses. In 2023 alone, Malappuram reported two deaths linked to the virus. Of all the confirmed infections since 2018, only six individuals have survived, underscoring the virus’s high mortality rate and the need for rapid medical intervention.

How the Virus Is Contracted?

Nipah virus is a zoonotic pathogen, meaning it spreads from animals to humans. Scientific investigations from previous outbreaks, including a joint field survey by the National Institute of Virology (NIV) and the National Institute of High Security Animal Diseases (NIHSAD), found a clear link between fruit bats (commonly known as flying foxes) and human infections.

The virus strain detected in Kerala is closely related to the Bangladeshi strain, notorious for its person-to-person transmission and high mortality, estimated by experts to be up to 90% in some cases. In the 2023 outbreak, antibodies were found in fruit bats from Pandikkad village, strongly pointing to them as the source of the infection.

The consumption of contaminated fruits or exposure to bat saliva and urine on fruits is believed to be one of the primary routes of transmission in initial cases.

What is Nipah Virus?

First identified in Malaysia in 1998, Nipah virus gets its name from the village of Sungai Nipah, where the initial outbreak occurred. The virus belongs to the Henipavirus genus and has since been recognized as one of the world’s most dangerous pathogens due to its pandemic potential and high case fatality rate — estimated to range between 40% and 75%, depending on the outbreak response and healthcare access.

Early symptoms are often non-specific and include:

- Headache

- Muscle pain

- Vomiting

- Sore throat

As the disease progresses, some patients experience acute respiratory distress, neurological complications like encephalitis, seizures, and altered mental states, which may rapidly lead to coma or death.

Is the Virus Contagious and Airborne?

Yes, Nipah virus is both contagious and airborne. It spreads primarily through respiratory droplets, bodily fluids such as saliva, urine, feces, and blood, and via direct contact with infected individuals or animals.

Healthcare providers and family members caring for infected patients are particularly at risk. This is why strict infection control measures, including personal protective equipment (PPE) and isolation protocols, are crucial to preventing person-to-person spread.

Why Prevention Is Critical?

Currently, there is no specific antiviral treatment or licensed vaccine available for Nipah virus. Medical care is supportive and symptomatic, focusing on:

Hydration and rest

Medications for fever and pain (e.g., acetaminophen, ibuprofen)

Treatment for nausea, seizures, and respiratory distress

Use of inhalers or nebulizers in case of breathing difficulties

Experimental therapies, such as monoclonal antibody treatments, are under research but not yet widely accessible. Given the lack of curative options, early detection and containment remain the most effective ways to manage an outbreak.

Containment Measures Followed in Kerala

Since the first outbreak, Kerala’s public health system has developed a robust protocol to respond to Nipah cases. Isolation wards, contact tracing, and real-time epidemiological surveillance are quickly deployed. The state has also worked closely with central agencies like NIV and WHO to bolster its diagnostic and response capabilities.

With this latest case in Malappuram, authorities are already mobilizing rapid response teams to trace contacts, disinfect the patient’s surroundings, and educate the public about symptoms and preventive measures.

Although most outbreaks have been localized to South and Southeast Asia, Nipah virus is considered a global threat. The World Health Organization (WHO) includes it on the list of priority diseases for research and development, due to its potential to cause widespread epidemics and the lack of available countermeasures.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also closely monitors Nipah virus, emphasizing the importance of global health surveillance systems. As climate change, deforestation, and wildlife trade continue to increase human-animal interactions, the risk of zoonotic spillovers like Nipah is on the rise.

The emergence of a new Nipah case in Kerala is a critical reminder of the interconnectedness of human and animal health. While the virus is not currently spreading globally, the high fatality rate, airborne nature, and lack of treatment options make it essential to remain vigilant.

For residents in affected areas and globally the best approach is a combination of early reporting, awareness about transmission, and adherence to public health guidelines.

Measles Outbreak In US Surge To 1,000 Cases; What If Herd Immunity Is No Longer Enough?

More than 1,000 measles cases have been confirmed across the United States in 2025, a saddening milestone of the nation's struggle with a disease it was officially announced as eliminated as far back as the year 2000. State and regional health agencies along with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report at least 1,002 cases so far this year—an astonishing number putting 2025 on pace to equal 2019, which was the century's worst measles year to date.

Most of these instances are a result of a fast-growing outbreak with its hub in West Texas, which has already spread to New Mexico, Oklahoma, and potentially Kansas. With underreporting anticipated and additional states preparing for increasing numbers, the true extent of this crisis may be much greater than present numbers indicate.

Measles was officially eliminated in the U.S. in 2000, thanks to extensive vaccination campaigns and strong public health infrastructure. During the past two decades, the nation experienced comparatively low case numbers—approximately 180 per year on average.

But the peace was broken in 2019, when 1,274 cases appeared during large outbreaks in New York City and surrounding communities. After a temporary hiatus during the COVID-19 pandemic, cases of measles started creeping back up again, peaking in this year's record-breaking increase.

The 2025 outbreak is particularly concerning because it implies systemic vulnerabilities in immunization coverage and public health readiness. Recent statistics show that just 4% of reported cases involved vaccinated individuals, affirming the vaccine's effectiveness but also highlighting the increasing numbers of individuals opting to forego vaccination altogether.

This resurgence is not confined to the United States. Across the Americas and parts of Europe, measles rates are rising sharply. In Canada, over 1,000 cases have been confirmed, a stunning leap from just 12 cases in 2023. Mexico has also reported over 400 confirmed cases, with additional suspected infections under investigation. In Europe, measles rates are now at their highest level in 25 years.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has raised alarms for both North and South America as high-risk areas, attributing declining vaccination levels, post-pandemic health disruption, and global mobility as main drivers for this resurgence.

Why Is Measles So Dangerous?

Measles is not an innocent childhood disease—it is extremely contagious and can result in severe complications, such as pneumonia, brain swelling (encephalitis), blindness, and even death. Three deaths—two of them children—have already been reported in the U.S. this year alone. The 2025 hospitalization rate is around 13%, highlighting the severity of the disease.

The basic reproduction number (R0) of measles—the number of individuals an infected person will, on average, transmit the virus to—is between 12 and 18, far more contagious than influenza or even COVID-19. Such high transmissibility makes vaccination not merely critical, but critical for disease control.

The present epicenter of the outbreak, Texas, has seen 702 confirmed cases in 29 counties, with 91 hospitalizations and three deaths as of May 6. What began as a localized cluster has blown up into a full-blown epidemic—illustrating just how rapidly measles can get out of hand in under-vaccinated communities.

Other states with significant outbreaks are Ohio, Montana, and Michigan, all having over three connected cases—the CDC's criteria for classifying an outbreak.

What If Herd Immunity Is No Longer Enough?

Herd immunity works because of a threshold level of the population (about 95%) getting vaccinated to safeguard those who are unable to be vaccinated because of age, allergy, or pre-existing medical conditions. The principle is quite simple: if enough individuals are immunized, the virus cannot circulate freely, and high-risk groups are still protected.

What Happens When Vaccination Rates Fall?

Current evidence indicates that this is occurring. In certain populations, immunization rates have collapsed as a result of refusal to be vaccinated and misinformation campaigns, stripping away the protective barrier that previously held back measles. The consequences are serious:

- Local outbreaks rapidly develop into regional epidemics, particularly in crowded or highly mobile populations.

- High-risk groups, such as infants, the immunocompromised, and the elderly, are put at increased risk.

- Healthcare systems get overwhelmed with avoidable diseases, sucking resources that could be used for other emergencies.

- As community immunity is lost, endemic transmission—where measles becomes perpetually present year after year—becomes an imminent possibility.

A 2025 study puts the current rate of vaccination at an estimate of 850,000 cases of measles over the next 25 years if it continues as is. With declining vaccine use, this figure could reach 11 million. They're not theoretical predictions—they're evident warnings based on facts.

Individual responsibility is not something to be substituted with herd immunity. If everyone is exempting themselves, the defense is lost. Even then, the immunized individuals stand to suffer as well due to sheer virus burden and possibility of breakthrough cases in compromised hosts.

How to Strengthen Yourself and Prevent Measles Spread?

For undoing this dismal trend, concerted action from public health officials at the earliest is paramount. This comprises:

- Public education campaigns to combat misinformation.

- School vaccination requirements and more stringent exemption policies.

- Improved surveillance and reporting systems to monitor outbreaks in real-time.

- Support for international immunization efforts, since infectious diseases do not recognize borders.

Programs such as Vaccines for Children have long assisted in keeping immunization rates high. Reinvesting in and updating these programs will be critical in avoiding future outbreaks.

The U.S. stands at a crossroads. The 2025 measles outbreak is more than a public health tale—it's an alarm call. Having a disease be "eliminated" does not equate to having won the war. In a time of international mobility, vaccine reluctance, and fractured public confidence, we have to recall that prevention is only effective if we all move together. Herd immunity used to suffice. It might not anymore.

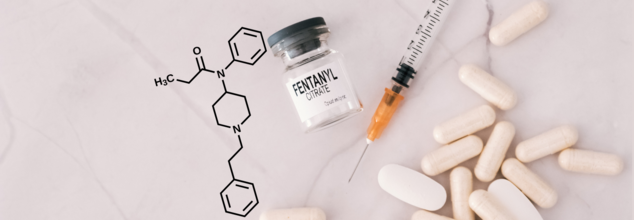

What Is The Fentanyl Seized In US Drug Bust Of 3 Million Pills? Uses, Warnings And Side Effects Explained

In the biggest drug crackdown, US authorities have seized more than three million pills—the largest fentanyl drug seizure in DEA history. The bust, which resulted in the arrest of 16 people, allegedly dismantled a large drug trafficking operation associated with Mexico's brutal Sinaloa cartel. This historical seizure underscores not just the magnitude of the synthetic opioid epidemic engulfing America but also the ghastly strength of fentanyl itself- a substance causing thousands of overdose fatalities every year.

The biggest fentanyl seizure in DEA history is both a victory and an admonition. It highlights the magnitude of the threat and reminds us that one pill, one dose, is potentially lethal. As a world community, we need to come together on solutions that meet medical demand and public safety before more lives are lost to an opioid that brings pain relief at one end and fatal dependency at the other.

As we make our way through the implications of this large-scale federal operation, it is important to know what fentanyl is, why it's so lethal, and how it is being abused globally.

What is Fentanyl?

Fentanyl is a man-made opioid initially designed for pain control, particularly for patients who are having major surgery or who suffer from extreme chronic pain. FDA-approved, it is a quick-acting narcotic painkiller that is almost 100 times more powerful than morphine and 50 times more potent than heroin. In a clinical setting, fentanyl is given by experts by injection, transdermal patches, or lozenges under close supervision.

Yet beyond the edges of clinical usage, fentanyl has become a public health debacle.

On the street, fentanyl is disguised under innocently sounding names like Dance Fever, China Girl, Goodfellas, Tango & Cash, and Murder 8. The names sound innocuous, but they cover up a lethal reality. Traffickers are now cutting fentanyl with other drugs like heroin and cocaine or stamping it into fake pills that look just like prescription drugs like oxycodone and Xanax—so that unsuspecting users can't tell what's harmless and what's deadly.

The three million fentanyl-contaminated pills taken by the DEA were suspected of being produced in clandestine labs, most likely using precursors purchased in China and processed by Mexican drug cartels.

How Fentanyl Is Taken and Why That Makes It More Dangerous?

Illegal fentanyl is ingested in so many different ways—smoking, snorting, swallowing in pill or tablet form, absorption using blotter paper, or taking with transdermal patches. The number of ways it is ingested raises the risk of overdose since users do not know how much fentanyl they are actually taking.

Worst still, users often think they're taking a less powerful drug when, in reality, they are taking a medication that can suspend their breathing in minutes.

What Happens to the Body When You Use Fentanyl?

Initial effects of fentanyl are similar to other opioids: pain alleviation, elation, and profound relaxation. But the danger profile is so much higher with its potency. Side effects could be:

- Sleepiness and giddiness

- Confusion

- Nausea and vomiting

- Sedation

- Respiratory depression

- Pupillary constriction (pinpoint pupils)

Symptoms in overdose situations can rapidly increase and may include:

- Stupor or coma

- Cold, clammy skin

- Blue lips or nails (cyanosis)

- Slow or ceased breathing to a dangerous level

These symptoms can lead to death in just minutes if not treated immediately with naloxone, an opioid antagonist.

Medical Use vs Misuse of Fentanyl

Care needs to be made between the use of fentanyl in a medical setting and abuse. In the hospital and tightly controlled medical environment, fentanyl is an essential drug for patients with pain that is resistant to other opioids. It's carefully given in minute amounts and while closely monitored.

Patients on fentanyl for pain control must be carefully watched for tolerance—a situation in which the same dose, over time, becomes less potent and dependency. Tolerance does not equal addiction, though. Under medical direction, fentanyl can be safely tapered off in order to prevent withdrawal symptoms.

Physicians also caution patients to not stop taking the drug abruptly, as it can cause withdrawal, which while not fatal, is very painful.

What are the Side Effects Of Fentanyl Use?

Aside from immediate effects, long-term fentanyl use—even when prescribed—can interfere with the body's natural hormone balance, decrease adrenal function, and cause muscle rigidity or hypotension (low blood pressure). In extreme cases, allergic reactions can occur, such as swelling of the face or throat, which needs emergency treatment.

The users should seek consultation with their care team if they experience symptoms such as nausea, unexplained fatigue, or difficulty staying awake—indications that the drug is impacting their central nervous system or endocrine system.

The record-breaking seizure by the DEA is a critical milestone, but it’s just one chapter in an ongoing battle. The opioid epidemic, fueled in large part by fentanyl, claimed more than 70,000 American lives in recent years, and the problem shows no signs of abating.

Public health professionals caution that education, awareness, and access to treatment are critical to stemming this crisis. Naloxone needs to be made widely available, and stronger international cooperation to break up the transnational supply chains facilitating fentanyl distribution is required.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited