- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

Do You Think You Have High Alcohol Tolerance? Here’s How Liquor Impacts Your Brain Activity

Liquor Impacting Brain Activity (Credit-Freepik)

Many of us believe that we are great drinkers and that alcohol does not affect us as much. People who are able to drink without showing any sign of inebriation are known as social drinkers. In short, they are not addicted to alcohol but will not turn down the opportunity to have a good time! While it may seem like it doesn’t affect you, new studies suggest that it is just an illusion, even if you have high tolerance, alcohol affects your cognitive and motor functions more than you think.

The study reveals the below implications and techniques:

- Researchers used a new MRI technique to precisely measure brain electrical activity.

- By comparing brain scans before and after drinking, scientists identified specific areas affected by alcohol and how much brain activity slowed down.

- Participants were chosen to be regular social drinkers without alcohol addiction, ensuring the study focused on the effects of alcohol alone.

- MRI technology provided reliable data on brain activity changes caused by alcohol consumption.

How does the brain react to alcohol?

The human brain is a complex network of billions of neurons that communicate through electrical impulses. Brain conductivity refers to the efficiency with which these electrical signals travel through brain tissue. It's akin to the speed and clarity of a digital signal through a wire. In layman terms, your brain must function in its peak condition as it is essential for various cognitive processes, including memory, attention, decision-making, and motor control.Think of it as the foundation for your brain's performance. When brain conductivity is high, information flows smoothly, and that helps your brain in rapid processing and response. On the other hand, low conductivity can hinder cognitive function, leading to slower thinking, impaired memory, and difficulties with coordination.

A study conducted at the Neuroscience Research Australia (NeuRA) and UNSW Science unveiled a startling connection between alcohol consumption and brain conductivity.

What is the connection between alcohol consumption and brain activity?

While many people brush off the effects of alcohol as temporary changes in behaviour, the reality is much more complex. Beyond the obvious impacts on coordination and judgment, alcohol significantly alters brain function. Alcohol dramatically slowed down brain activity, especially in areas responsible for decision-making, planning, and physical coordination. This decline was so significant that it resembled the brain changes seen in normal ageing. This means even one drink could temporarily accelerate the ageing process of your brain.

Alcohol and Brain activity: What does the study Imply?

The implications of this research are far-reaching. It provides compelling evidence that alcohol consumption has a direct and measurable impact on brain function. The discovery that alcohol can significantly reduce brain conductivity opens new avenues for understanding the neurocognitive effects of alcohol abuse and dependence. While you may not feel like alcohol is affecting you and you have a high tolerance, it most definitely changes and affects your decision-making abilities and impulse control.

Furthermore, the MRI technique employed in the study could be a valuable tool for assessing the impact of other substances on the brain and for developing interventions to mitigate alcohol-related brain damage.

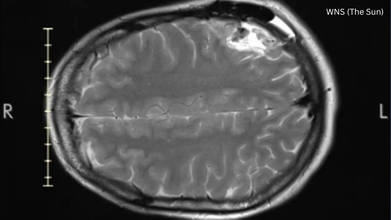

Lauren Macpherson Brushed Off Her Symptoms as ADHD, Turns Out She Had Terminal Brain Cancer

Credits: WNS (The Sun)

Lauren Macpherson, 29, started showing symptoms of what she later realized was terminal brain cancer after a heavy case fell from the luggage rack of a train on her head. She had to be rushed to hospital. She was on the train for a music festival in London and had to be taken off halfway due to excruciating pain. She had instant swelling and doctors feared that she had a fracture in her spine or a concussion. However, scans revealed something else. There was a shadow on her brain, which turned out to be a tumor. She was told that she only had 12 months to live.

“As [the doctor] said it I just knew, because I’ve been having all these symptoms building up, especially over the last two years, and it just clicked. There is an instinct inside you, and when you have been feeling unwell, it just all made sense,” said Lauren.

Lauren Dismissed Her Symptoms As ADHD

She revealed that she had been suffering from a series of symptoms like extreme fatigue, bad memory, emotional dysregulation, stomach pain, and headaches. She however, believed that these symptoms were linked to ADHD (attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder). This condition is also characterized by behavioral differences like difficulties with focus.

Surprising to most, being told that she had a brain tumor was a "relief" to her. "You think you are going crazy, all these things going wrong. I would have such bad days where I literally could not get out of bed. Like nobody would understand," she said.

Read: Colon Cancer Is The Leading Cause Of Death In US For People Under 50

Doctors had told her in September 2025 that she may have less than a year to live. "I just kept saying, 'just give me my thirties'. I will be grateful for anything just as long as I get my thirties and it gives me time to just say goodbye and have a bit of a life," she said.

“That’s all I could think about. I couldn’t think of anything else, it was just get through it, to get through my thirties and that is all."

The Condition Lauren Has

A biopsy showed that she had oligodendroglioma. This is a rare type of tumor that develops in the glial cells. She was told that the average life expectancy of such a tumor is around 10 to 12 years.

Last year, in October, she had a six-hour awake craniotomy at a private clinic in London. While surgeons were able to remove 80 per cent of the tumor, she struggled with memory loss afterwards.

"I couldn’t speak and didn’t even know how to unlock my phone,” she wrote in a blog post for Brain Tumour Research. "Slowly, my memory and speech returned. I still can’t read or write properly and I’m undergoing rehabilitation. I still search for words during conversation and get headaches, but things are improving," she wrote.

She now wants to live her live to full with what time she has left and is planning to marry her partner Zac and enjoy a trip to Italy to mark her 30th birthday.

UP partners with Wadhwani AI to improve TB care, telemedicine, maternal and child health

Credit: Wadhwani AI

The Uttar Pradesh Government today announced a partnership with Wadhwani AI to develop a roadmap for deploying a suite of AI-powered solutions across the state’s public health programs.

The partnership will advance the deployment of seven AI-powered solutions, such as:

- tuberculosis care and management

- telemedicine

- eye health

- maternal and child health

- equipping frontline health workers with data-driven tools

Wadhwani AI will serve as a technical partner to the state, supporting the deployment of AI-driven tools aligned with the government’s public health priorities.

The collaboration aligns with the UP AI Mission -- a three-year initiative launched by the UP Government to build a state-led AI ecosystem and accelerate the use of AI across sectors, including governance, healthcare, and agriculture.

“AI offers a promising opportunity to further enhance efforts by supporting frontline health workers, improving early disease detection, and enabling more informed clinical decision-making,” said Amit Kumar Ghosh (IAS), Additional Chief Secretary, Medical Health, Family Welfare, and Medical Education in Uttar Pradesh.

“Through this partnership with Wadhwani AI, we look forward to adopting and deploying AI-driven tools across our health programs and progressively expanding the use of these solutions to further strengthen service delivery and improve health outcomes across the state,” Ghosh added.

The AI-powered Solutions

- In tuberculosis care, the Cough Against TB (CATB) mobile phone-based screening application will enable frontline healthcare workers to identify individuals with presumptive pulmonary TB by analyzing cough sounds and accompanying symptoms, enabling early detection even in community settings.

Vulnerability Mapping for Tuberculosis (VMTB) will use geospatial AI analytics to identify high-risk locations by analyzing TB program data alongside multiple environmental and health indicators, helping health authorities prioritize targeted interventions and active case-finding activities.

The Prediction of Adverse TB Outcomes (PATO), an AI-powered risk stratification tool, will help identify patients at higher risk of adverse outcomes at the onset of TB treatment and facilitate prompt, targeted, and effective interventions that, over time, will help lower mortality rates and prevent drug-resistant TB.

- In telemedicine, the Clinical Decision Support System (CDSS) will enable clinicians to access structured patient information and offer AI-assisted differential diagnosis recommendations during consultations, supporting the quality and consistency of care delivery across primary healthcare settings.

- The collaboration will also include the deployment of Health Vaani, a voice- and text-based knowledge assistant which will provide frontline health workers with instant access to government-approved health guidelines, enabling quicker decision-making and more consistent service delivery at the community level.

- To address the growing burden of diabetes-related vision complications, the partnership will also deploy MadhuNetrAI, an AI-enabled screening solution that will analyze retinal images to detect diabetic retinopathy and support early referral for specialist care, particularly in resource-constrained settings where specialist availability may be limited.

- In maternal and newborn health, Shishu Maapan, an AI-powered newborn anthropometry tool, will enable frontline health workers to capture accurate newborn measurements using a smartphone during home-based newborn care visits.

“The solutions being deployed span the continuum of health delivery from identifying high-risk communities to supporting ASHA workers during field visits, to enabling early disease detection through AI-assisted analysis,” said Dr. Neeraj Agrawal, Chief Program Officer, Wadhwani AI.

"As the partnership progresses, we look forward to expanding this work and supporting additional AI solutions that can further strengthen health systems and improve outcomes at scale," he added.

Certain Antibiotics May Alter Gut Microbiome for Up to Eight Years, Study Finds

Credits: Canva

Antibiotics have long been considered lifesaving medicines, especially when it comes to treating serious bacterial infections. However, scientists have also known for years that these drugs can disturb the gut microbiome, the vast community of bacteria that live in our digestive system and play an important role in overall health. Now, new research suggests that the impact of some antibiotics on the gut may last far longer than previously believed.

A recent study has found that certain antibiotics may alter the gut microbiome in ways that persist for up to four to eight years after treatment. The findings were reported by scientists from Sweden and published in the journal Nature Medicine. According to the researchers, these long lasting changes may reduce the diversity of bacteria in the gut, which could potentially influence health over time.

Long term changes in gut bacteria

The gut microbiome contains hundreds of different species of bacteria that help regulate digestion, immunity, metabolism and even aspects of mental health. A healthy gut microbiome usually has a wide variety of bacterial species. When this diversity decreases, it may make the body more vulnerable to several health conditions.

Scientists have previously linked lower microbial diversity in the gut to problems such as obesity, diabetes and inflammatory bowel disease. Because antibiotics kill bacteria to fight infections, they may also eliminate beneficial microbes along with harmful ones. In some cases, this imbalance may take a long time to recover.

In the new study, researchers identified specific antibiotics that appeared to have the strongest and most lasting effects on gut bacteria. These included clindamycin, fluoroquinolones and flucloxacillin. The study’s lead investigator said that these medications were associated with significant changes in the overall composition of the gut microbiome.

Researchers observed that some bacterial species declined after antibiotic exposure while others increased. This shift altered the balance of the microbial community and was linked to reduced diversity.

Comparing antibiotic users and non users

To understand the relationship between antibiotics and gut bacteria, the research team analysed data from Sweden’s National Prescribed Drug Register. They then compared this information with gut microbiome samples from 14,979 adults living in Sweden.

The scientists examined the microbiome of people who had been prescribed different antibiotics and compared it with those who had not received any antibiotics during the same period.

Their analysis revealed that some antibiotics had stronger long term effects than others. For instance, penicillin V, one of the most commonly prescribed antibiotics for infections outside hospitals in Sweden, appeared to cause shorter lasting changes in gut bacteria.

However, other antibiotics were linked to more persistent shifts in the microbial ecosystem.

Effects that last for years

One of the most striking findings of the study was how long the effects could remain visible. According to the researchers, antibiotic use from four to eight years earlier was still associated with differences in a person’s gut microbiome.

Even a single course of certain antibiotics appeared to leave detectable traces years later. While the exact biological mechanisms are still not fully understood, the researchers believe antibiotics may permanently reshape parts of the microbial community in some individuals.

What this means for future antibiotic use

The researchers believe their findings could help guide future decisions about prescribing antibiotics. If two antibiotics are equally effective against an infection, doctors may eventually consider choosing the one that has a weaker impact on the gut microbiome.

Such insights could help balance the need to treat infections while also protecting long term gut health.

To better understand how the microbiome recovers over time, the scientists are now collecting a second set of gut samples from nearly half of the participants involved in the study. This follow up analysis may reveal how quickly the microbiome can recover after antibiotic exposure and which individuals may be more vulnerable to long lasting disruptions.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited