- Health Conditions A-Z

- Health & Wellness

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Health News

- Ayurveda

- Videos

- Medicine A-Z

- Parenting

Why Your Waistline Tells More About Your Body Composition Than BMI- Ways To Trim Down Fat

BMI has been the benchmark in evaluating health and fitness for many years. The formula is quite simple: weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. This would easily tell if one is underweight, within the healthy weight range, overweight, or obese. But with new research findings, scientists are now questioning its accuracy and usefulness as a total measure of body composition.

The report, published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, has sparked a global conversation on rethinking BMI. Supported by more than 50 international medical experts, the report suggests classifying obesity into "clinical" and "pre-clinical" types for better diagnosis and treatment. The shift underscores a growing consensus: BMI alone may not tell the full story of your health.

While BMI is simple to calculate and universally accessible, it is far from perfect. It does not consider muscle mass, bone density, or fat distribution, leading to misleading conclusions in some cases. For example, athletes with a high muscle mass may be considered overweight, whereas individuals with normal BMI might carry unhealthy amounts of visceral fat.

A landmark study in JAMA Network Open studied more than 155,000 postmenopausal women and found that women with a normal BMI but a waist size over 35 inches were more likely to die from heart disease or cancer compared with their counterparts whose waists are smaller. That makes a great case for how BMI can be insufficient and fat distribution must be factored into account.

Not all body fat is equal. Subcutaneous fat, which lies just beneath the skin, is relatively harmless. The real health danger lies in visceral fat—fat that surrounds internal organs. Unlike subcutaneous fat, visceral fat is metabolically active, releasing stress hormones like cortisol and inflammatory substances that raise blood pressure, blood sugar, and cholesterol levels. These effects significantly increase the risk of conditions such as heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and certain cancers.

BMI Isn't Always the Best Measure of Body Composition — Here's What to Use Instead

Since BMI is not the most reliable measure, scientists and doctors have sought other means to measure body composition more accurately.

1. Waist Circumference

A simple tape measure can provide valuable insight into your health. Measure your waist at the level of your belly button, ensuring the tape is parallel to the ground. For women, a waist measurement under 35 inches is considered healthy, while for men, the goal is under 40 inches.

2. Waist-to-Hip Ratio

This is the ratio of your waist circumference to that of your hips. To calculate it, divide your waist measurement by your hip measurement. According to the National Center for Biotechnology Information, a ratio under 0.8 for women and 0.9 for men is considered healthy.

3. Body Roundness Index (BRI)

A newer method that seems to be receiving more attention involves the Body Roundness Index or BRI: height, weight, and girth are placed together to represent a more advanced view of what body composition says. Research presented in JAMA Network Open offers evidence that this BRI predicts mortality risk greater than BMI in some cases- a promising weapon for public health.

Also Read: Using BMI To Classify People As Obese Is Flawed Say Experts

Ways To Cut Off Unhealthy Fat

The good news is that visceral fat responds well to lifestyle changes. Here are three evidence-based strategies:

Time-Restricted Eating

Adopting an eating window of 12 hours—such as from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m.—can significantly reduce visceral fat, according to a study published in Nutrition Research Reviews. This approach not only helps control caloric intake but also reduces late-night snacking, a known risk factor for abdominal obesity.

Limit Alcohol Intake

Excessive alcohol consumption is associated with increased belly fat. A 2017 study published in Public Health Nutrition revealed that alcohol increases the levels of insulin and encourages the storage of fat in the abdominal area. Limiting alcohol to occasional indulgence helps avoid weight gain in this region.

High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT)

HIIT involves repeated episodes of high-intensity exercise separated by periods of rest. A review in *Sports Medicine* concluded that HIIT is very effective in reducing visceral and total body fat. It can be noted that adding just 20 minutes of HIIT two times a week can make all the difference.

The reliance on BMI as a sole indicator of health is increasingly being challenged. While it remains a convenient screening tool, its limitations necessitate a broader approach that considers factors like fat distribution, waist circumference, and new metrics such as BRI.

In the simplest of words, health is multi-dimensional, and shifting perspectives from considering weight solely to broader measures of body composition will get people a much clearer understanding of where their health risks are so that they can take the action required for a better quality of life. Through adjustment to diet, exercise, or perhaps through innovative metrics like BRI, health is well within reach of the individual.

This dynamic conversation raises the point about personalized health screenings, which helps everyone get more relevant tools fitting their unique lives and circumstances. As body composition research is enhanced, so do the futures look brighter and brighter for the times of measurement when it comes to health.

Definition and diagnostic criteria of clinical obesity. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology.

Association of Normal-Weight Central Obesity With All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality Among Postmenopausal Women. JAMA Netw Open. 2019

Waist-Hip Ratio. NIH.

Physiological responses to food intake throughout the day. Nutr Res Rev. 2014

Association between abdominal obesity and alcohol drinking pattern in normal-weight, middle-aged adults. Public Health Nutr. 2017

Can Too Much Running Worsen PCOS? Gabby Logan Opens Up About Athlete Daughter’s Diagnosis

Credits: Instagram

British broadcaster Gabby Logan has revealed that her 20-year-old daughter Lois has been diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), a hormonal condition that may require her to step back from high-intensity endurance sport, including extreme long-distance running.

Speaking on her Mid-Point podcast, Logan said the diagnosis came after medical consultations about her daughter’s health and training. During the appointment, a specialist advised Lois to avoid “extreme running,” prompting mixed emotions in the family, concern about the condition, but also relief about scaling back punishing physical goals.

What PCOS Means for Athletes

PCOS is one of the most common endocrine disorders in women of reproductive age, affecting an estimated 8–13 per cent globally. It occurs when the body produces higher levels of androgens (male-type hormones) and often involves insulin resistance.

The condition can cause irregular periods, acne, excessive hair growth, weight changes and fertility challenges. Many patients also have difficulty regulating blood sugar, increasing long-term risks of type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

While exercise is widely recommended as a cornerstone of PCOS management, helping improve insulin sensitivity, metabolism and mood, specialists say the type and intensity of exercise matter.

Why Extreme Endurance Could Be A Problem

Doctors cautioned Lois against extreme endurance events such as half-marathons because prolonged, high-intensity training can significantly elevate cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone.

In people with PCOS, hormonal balance is already fragile. Persistently high cortisol may:

- worsen insulin resistance

- disrupt ovulation further

- aggravate fatigue and inflammation

- intensify menstrual irregularities

In other words, although movement is beneficial, chronic physical stress can sometimes counteract the hormonal stability patients are trying to restore.

Moderate-intensity exercise, brisk walking, strength training and shorter runs, is generally considered more supportive for hormone regulation than sustained high-intensity endurance workloads.

From Half Marathon To Shorter Goals

Logan previously completed the London Landmarks Half-Marathon with Lois in 2024, describing the preparation as mentally and physically demanding. The pair had hoped to repeat the experience, but the new medical advice has changed those plans.

Instead, they now intend to focus on shorter runs together.

The television presenter admitted she felt a surprising sense of relief at the specialist’s recommendation, recalling how intense the training had been for both of them.

A sporting life continues — just differently

Lois, a competitive showjumper and university student, has long balanced academics with elite sport. She has ridden horses since childhood and competed at national levels, later even participating in a charity jockey race — an experience she described as “brutal.”

Her diagnosis does not end her athletic pursuits, but it reshapes them.

Medical experts increasingly stress that PCOS management is not about stopping exercise but tailoring it. Sustainable training, adequate recovery, and balanced nutrition often produce better long-term hormonal outcomes than relentless endurance performance.

For athletes with PCOS, the goal shifts from pushing physical limits to supporting physiological stability — a change that, doctors say, can ultimately protect both performance and health.

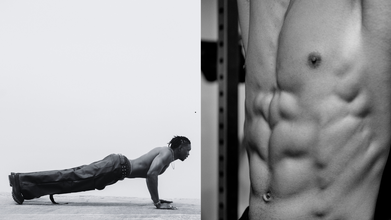

Are Abs And Core The Same Thing?

Credits: Canva

You must have heard people say, "Tighten those abs!' "Engage you core!" However, have you ever wondered what it really means? Are they the same thing? Is there a difference?

While "abs" and "core" tend to be used synonymously, the reality is that one is simply the exposed tip of the iceberg and the other, a dynamo driving your whole body's power and stability. Whether you're after a six-pack or just want to move with less pain and more power, knowing how your abs differ from your core might entirely overhaul how and why you train.

Although these terms are thrown about as if synonymous, they literally address different muscle groups with redundant but unique functions. And understanding the distinction might change how you train entirely not only for looks, but for functionality, posture, and strength in general.

You must have heard people say, "Tighten those abs!' "Engage you core!" However, have you ever wondered what it really means? Are they the same thing? Is there a difference?

While "abs" and "core" tend to be used synonymously, the reality is that one is simply the exposed tip of the iceberg and the other, a dynamo driving your whole body's power and stability. Whether you're after a six-pack or just want to move with less pain and more power, knowing how your abs differ from your core might entirely overhaul how and why you train.

Although these terms are thrown about as if synonymous, they literally address different muscle groups with redundant but unique functions. And understanding the distinction might change how you train entirely not only for looks, but for functionality, posture, and strength in general.

Abs vs. Core: What's the Real Difference?

Most everyone has an idea of what abs are when they hear the term, it's all about that coveted "six-pack." But abdominal muscles are more than vanity points.

These are the rectus abdominis (for the six-pack appearance), the external obliques and internal obliques (for side bending and twisting), the transversus abdominis (lowermost layer stabilizing the spine), and the pyramidalis (a small muscle located close to the pubic bone).

Found in the front of your body, these muscles assist in the protection of internal organs, aid in posture, and create forward bending and twisting actions.

Visualize your core as the inner strength system of your body. It's not just the abs a larger, more comprehensive area that encompasses pelvic floor, diaphragm, back extensors, obliques, and even hip flexors. The core stabilizes your entire trunk, supports your spine, and facilitates coordinated movement. Whether lifting groceries or marathoning, your core provides balance and injury protection.

So while abs are part of your core, a solid core is so much more than toned midlines—it's your body's anchor.

Why Engaging Your Core Matters More?

If you’ve ever heard a trainer say “engage your core” and wondered what it really means, here’s the truth: core engagement isn’t just about tensing your stomach. It's about bracing your midsection in a way that stabilizes your spine without holding your breath or excessively sucking in.

Done right, activating your core during workouts:

- Reduces strain on the lower back

- Protects joints and ligaments from injury

- Improves posture and balance

- Improves control and efficiency in movement

Most individuals unconsciously overcompensate by hinging backward at the hips or holding their breath—errors that can diminish the efficiency of a workout as well as heighten the risk of injury.

Pro tip: You ought to be able to breathe naturally while keeping a solid, braced core.

5 Highly Effective Ab Exercises

When exercising specifically for the abs, these exercises isolate the front abdominal wall and obliques:

Bicycle Crunches

One of the best exercises to work both the obliques and rectus abdominis. Lie on back, legs up to tabletop, and rotate opposite elbow to knee in pedaling motion.

Leg Raises

Works lower abs. Lie on your back, hands under your hips, and lift legs up to 90 degrees slowly, then return without contact with floor.

Russian Twists

Ideal for the obliques. Sit, lean back somewhat, raise feet (optional), and twist torso side to side holding a weight or medicine ball.

Reverse Crunches

Begin on your back, knees bent. Contract abs in order to lift hips off the ground while curling knees toward your chest.

Flutter Kicks

Lie on your back, raise both legs off the floor a few inches, and alternate kicking up and down. Keep your core tight the entire time.

These exercises are best for developing definition and endurance in your abdominal muscles—but don't begin and end there.

5 Highly Effective Core Exercises

To get your entire core stronger, from back to hips to pelvic floor, these compound exercises are the key:

Plank Variations

From forearm to side planks, this isometric exercise uses every muscle in the core. Maintain hips level, spine neutral, and core braced.

Dead Bugs

Lie on back with arms and legs up. Lower opposite leg and arm slowly while keeping back flat. Works deep stabilizers.

Bird-Dog

On hands and knees, reach out opposite arm and leg. Great legs, lower back, and core stability exercise.

Glute Bridge with March

Lift hips up into a bridge, then alternate marching one foot at a time. Targets glutes, core, legs, and pelvic stabilizers.

Pallof Press

With a resistance cable or band, press hands straight out from chest resisting twisting. One strong anti-twist core exercise.

These training methods cause your body to function as a functional unit. Outcome? Less injury, improved posture, and enhanced performance in sports and everyday activity.

Should You Train Abs and Core Separately?

It all depends on your aim. If your main target is visual definition, ab-specific training along with proper nutrition and cardio is the priority. But for overall strength and spine development, incorporating core exercises into your regimen is not negotiable.

Your ideal weekly training schedule should have a balanced combination of both isolated ab exercises and compound core exercises. Isolated ab movements support the development of muscular endurance and play a role in visible muscle definition, especially in the rectus abdominis—the traditional "six-pack" muscle.

At the same time, compound core training addresses deeper stabilizing muscles that translate to overall strength, mobility, and spinal stability.

This integrated training not only enhances gym performance but also prepares your body to execute daily movement with more ease and efficiency. Knowing the distinction between abs and the core changes the way you train. It's not all about crunches—it's about developing a strong, functional center that stabilizes your whole body.

When you train for more than just looks and with core integrity, you minimize injury risk, enhance athletic performance, and feel stronger in day-to-day movements. So the next time you roll out on the mat, remember: engaging your abs is awesome, but strengthening your core? That's how you fuel your life.

Your Gym Weights Have More Bacteria Than A Toilet Seat

Credits: Canva

We walk into gyms thinking about gains. Stronger muscles, better stamina, maybe even that perfect mirror selfie. Everything looks clean, polished, and professional. But beneath that shiny surface lies an uncomfortable truth.

Studies reveal something alarming. Dumbbells can harbor 362 times more bacteria than a toilet seat, while fitness bikes may carry 39 times more bacteria than restaurant self-service trays. It sounds shocking, but the numbers tell a clear story. Your workout zone might also be a microbial playground.

Why Gyms Become Bacteria Hotspots

Gyms create the perfect environment for germs to thrive. Think about sweat, shared equipment, warm temperatures, humidity, and dozens of people rotating through the same machines every day.

Every time someone grips a dumbbell, lies on a mat, or adjusts a treadmill setting, they leave behind sweat, skin cells, and natural body oils. Multiply that by multiple users in just a few hours, and you have an invisible layer of bacteria building up.

Dr. Susheela Chaurasia, Consultant Microbiologist at Wockhardt Hospital, explains that gym equipment has several small crevices and surfaces that trap moisture and organic material. These warm and moist conditions create an ideal breeding ground for bacteria, viruses, and fungi.

Among the most common culprits found in gyms are Staphylococcus aureus, commonly known as staph, which causes skin infections, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which thrives in damp areas like locker rooms and can trigger respiratory or urinary tract infections.

Even with routine cleaning, high-touch surfaces remain vulnerable because equipment is constantly being reused.

When Workouts Come With Unwanted Side Effects

Have you ever returned home from the gym with an unexplained rash or irritation? It may not just be coincidence.

When you exercise, your pores open up and your immune system temporarily shifts focus. This can make it easier for bacteria to enter through tiny cuts, abrasions, or hair follicles. Wearing damp gym clothes for too long can also encourage fungal infections and skin irritation.

Frequent exposure to contaminated surfaces may increase the risk of recurring skin conditions, joint infections, or respiratory issues, especially in people with lower immunity.

It is not just gym members who are exposed. Trainers, staff, and cleaning crews operate in the same microbial environment daily. This increases the possibility of bacteria circulating within the space.

Read: Fact Check: Is Weight Lifting Safe for Teens?

Hygiene Is Your First Line of Defense

The good news is that you do not need to cancel your membership. You just need to be more mindful about hygiene.

Start with simple habits. Always wipe equipment before and after use. Use your own towel or mat to create a barrier between your skin and shared surfaces. Avoid touching your face during workouts. Wash your hands thoroughly once you are done. Change out of sweaty clothes immediately after exercising.

Experts stress that disinfection is more effective than basic sanitization when it comes to gym equipment. Non-porous surfaces like metal and plastic should be cleaned with recommended disinfectants because bacteria can survive in cracks or poorly cleaned areas.

Also, avoid walking barefoot in locker rooms, steam rooms, or pool areas, since these spaces are prone to fungal growth.

Do Not Bring the Gym Home

Your hygiene routine should not end when you leave the gym. Shoes worn outdoors and inside the facility can transfer germs onto your home floors. Keeping gym shoes separate or leaving them near the entrance can reduce this risk.

Shower soon after workouts, wash gym clothes regularly, and keep any cuts or wounds covered while exercising.

A Shared Space Means Shared Responsibility

Gyms are community spaces. Hygiene is not just personal but collective.

If you are feeling unwell, skipping a workout might actually be the healthier decision for everyone. Fitness is built through consistency, recovery, hydration, sleep, and balanced habits.

So the next time you pick up those weights, wipe them down first. Staying fit should never mean exposing yourself to unnecessary infections.

© 2024 Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited